This Cop Unleashed A Reign Of Terror, Say The Wrongfully Accused

For years, people in Raleigh were arrested for heroin possession—without having the drug. Now, they’re demanding answers

This article was produced in partnership with Rolling Stone.

The afternoon of May 21, 2020, Yolanda Irving was relaxing in her bedroom in East Raleigh, North Carolina. The city was in the throes of the Covid-19 pandemic, so her three kids milled around the apartment. Irving’s teenage daughter, Cydneea, was in her room across the hall, and her 20-year-old son, Juwan, was in his wheelchair playing video games. Outside, Irving’s youngest, Jalen, then 12, sat on the stoop with three teenage neighbors.

Suddenly, more than a dozen officers from the Raleigh Police Department’s Vice and Selective Enforcement Unit (SEU, the department’s version of SWAT) ran at the boys with riot shields and assault rifles, according to interviews and multiple lawsuits against the city of Raleigh. Thinking they were about to be shot, the boys ran inside for safety. Jalen darted into his mother’s apartment with his 16-year-old neighbor Ziyel. Jalen screamed, “SWAT! SWAT! Please don’t shoot! Please don’t shoot!”

As a few officers burst through Irving’s door, other agents pursued the two other boys, 15-year-old Ziquis and 18-year-old Dyamond, into the apartment of neighbor Kenya Walton. There, they held Ziquis, Walton’s pregnant 20-year-old daughter, and her autistic 15-year-old son at rifle point. They did the same thing in Irving’s apartment, even screaming at the wheelchair-bound Juwan to get on the floor.

“I kept trying to tell them that my son is handicapped, please don’t shoot,” Irving says. The officers didn’t relent until Juwan pulled up his pants to reveal the brace on his leg, showing them that it was impossible for him to comply. Down the hall, Irving’s daughter pleaded with the officers not to shoot their dog.

Walton, who was out picking up groceries for dinner, got a call from a friend that her apartment was under siege. When she arrived back home, an officer approached her with his gun drawn. He escorted her through the back door of her home.

Confused, Walton asked her kids, “What did y’all do?” She turned to the officers and repeatedly asked, “What did they do?”

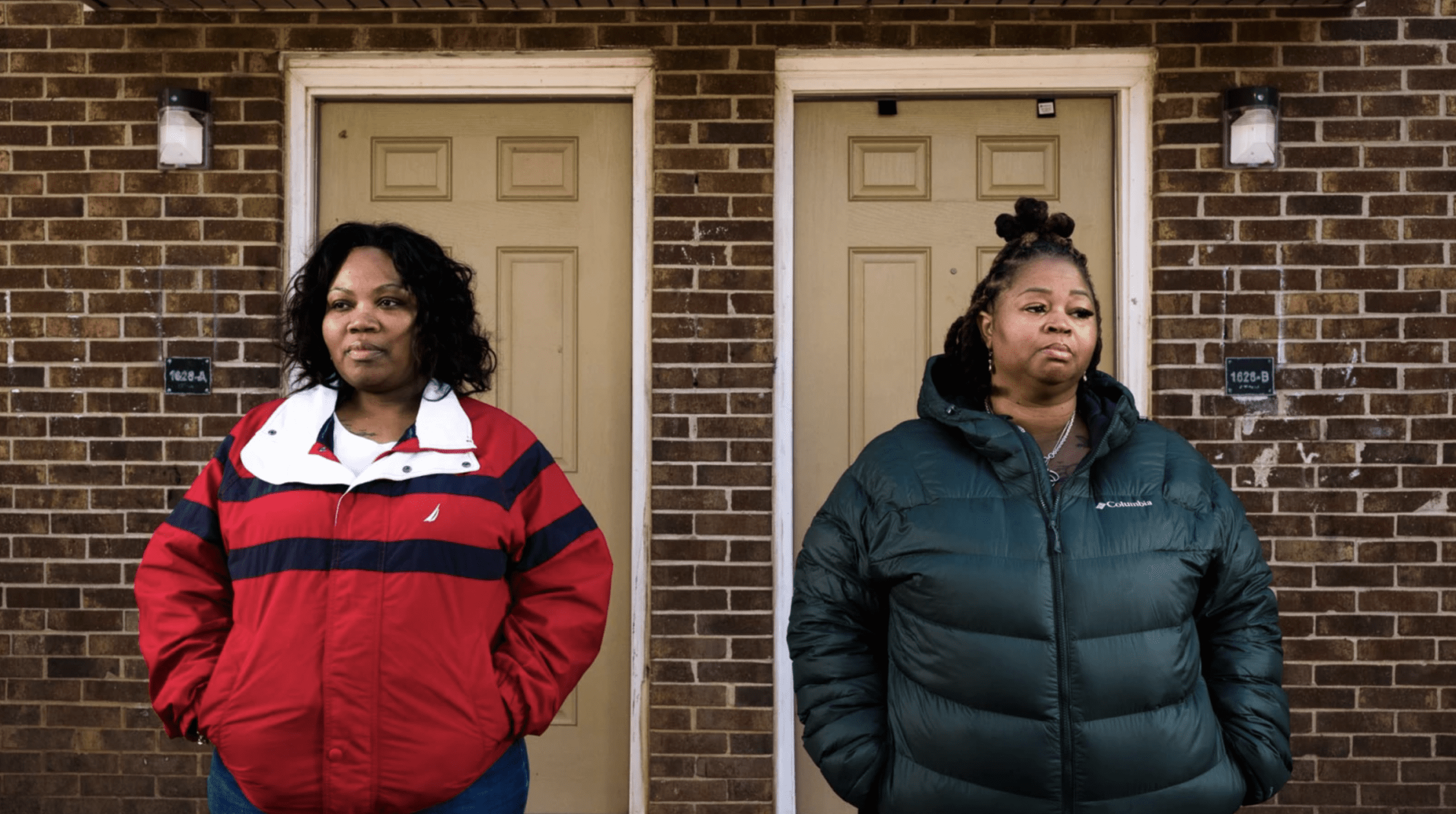

The officers searched the apartments for an hour and a half for heroin. They found nothing. Kenya Walton and Yolanda Irving are drivers for special-needs children. They aren’t heroin dealers. They’ve never even seen the drug.

Afterward, Omar Abdullah, the lead detective on the raid, briefly spoke with Irving and handed her the search warrant for her home. When Irving saw the photo for the residence attached to Abdullah’s warrant, she knew immediately: He had the wrong address. And Abdullah didn’t have a warrant at all for Walton’s home.

As Irving screamed curses at Abdullah for tearing up the wrong home, he simply turned and walked away. The RPD didn’t help her or Walton clean up, and the women say they have yet to receive an apology for the invasion.

The Vice and SEU raid was in fact meant for a man named Marcus Vanirvin, who lived a few hundred feet away in Irving’s apartment complex. As their homes were searched, the women saw police arrest him for heroin trafficking when he took out the trash. Then the cops searched his home but found no drugs. The Vanirvin arrest was supposedly based on controlled buys — undercover operations in which a confidential informant is sent to purchase heroin to form the basis for drug arrests — over the two prior months, incident reports show. Vanirvin denied ever selling — or even using — heroin, and after spending more than two weeks in jail, the charges were dropped.

Omar Abdullah was once considered RPD’s finest. He joined the department in 2009 and was named RPD Employee of the Year for 2012. In 2017, Abdullah was in his early forties when he was promoted to detective in one of the department’s Drug and Vice units. Once a detective, lawsuits allege, he terrorized the Black community in Raleigh through a series of narcotics arrests built on lies and fabricated evidence, with the help of an equally unreliable confidential informant. Nearly two dozen people are known to have been swept up in these arrests. All of his alleged victims were Black.

At least six men have had their convictions vacated after pleading guilty to drug charges in cases brought by Abdullah, and three federal civil rights lawsuits — including one stemming from the Irving and Walton raids — have been filed related to his police work.

Attorneys for one of Abdullah’s alleged victims estimate in a lawsuit that from Aug. 16, 2018, through May 21, 2020 — when Abdullah was suspended following the raid on the Irving and Walton homes — the officer and an informant “conspired to make at least 29 separate controlled buys, most if not all of which involved fake drugs or real narcotics that were planted on the alleged sellers.” The attorneys say that about half of these controlled buys resulted in cases that were dismissed because fake heroin was planted on people. In the case of the Irving raid, the “heroin” that was used to secure the warrant was likely brown sugar.

“It’s not just Abdullah who’s doing this, but there is evidence that a number of other officers either did it or knew it was being done and did nothing about it,” says prominent North Carolina civil rights attorney Bradley Bannon, who is not involved in the Raleigh lawsuits. “When there’s no consequence for something, the only thing you’re left with is just individual personal moral codes or consciences, and that’s never been relied upon by any society I’m aware of to regulate conduct.”

Specialized police units focused on narcotics and violent crime have been a fixture of modern policing since at least the 1980s, and have been notorious for violating people’s constitutional rights. In Atlanta, the Red Dog Unit (an acronym for Run Every Drug Dealer Out of Georgia), formed around 1988, was known for violence — including the killing of a 92-year-old woman during a botched drug raid in 2006 — before it was retired in 2011 and later rebranded as Titan. In Baltimore, the notorious Gun Trace Task Force ran the streets until a series of indictments ranging from robbery to drug dealing brought down the unit in 2017, and pulled the Baltimore Police Department into a federally mandated overhaul due to its civil rights abuses. (This misconduct is the subject of two books as well as an HBO limited series from David Simon.) Last fall, an internal probe of a “crime suppression team” in the Washington, D.C., police force led to prosecutors dropping charges in 65 gun cases. And in January this year, five police officers in Memphis’ Scorpion Unit were charged with murder for beating Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man, to death after a traffic stop. The furor over Nichols’ death prompted the Justice Department to launch an investigation into specialized units nationwide in March.

In Raleigh, lawsuits claim that multiple residences have been breached on faulty or fabricated evidence with no-knock or quick-knock warrants obtained in search of narcotics and executed with the aid of the SEU’s paramilitary officers — the same kinds of raids that led to the deaths of Amir Locke in Minneapolis last year and Breonna Taylor in Louisville in 2020. And since 2013, at least 12 people have been killed by RPD officers, all but one of them a person of color. In mid-January, a Black man was tased to death by Raleigh cops in a parking lot after police initiated a search because they thought he might have drugs. (The six officers were placed on administrative leave. Investigations by the police department and North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation are ongoing.)

Aside from Abdullah, the other constant in each of the dismissed cases is his confidential informant, Dennis Williams, who was unhoused in 2018 and desperate for cash.

That summer, Williams was arrested by Abdullah and another RPD officer for passing off aspirin as cocaine to a confidential informant. Despite having a lengthy and violent criminal history, Williams, then 24, was recruited to be an informant himself and paid for his services. The officers nicknamed Williams “Aspirin” and set him to work scouring the city for heroin peddlers virtually unchecked, according to lawsuits.

On Feb. 28, 2020, Gregory Washington drove with his brother to pick up his friend Diontre Greene and take him to work. Greene asked to pick up Williams on the way. They met Williams outside a Food Lion supermarket in East Raleigh, and he got into the back seat. Within moments, Washington says, Williams opened his door and frantically dashed across an open field near the parking lot. Washington threw his car in reverse to get away from whatever bad thing he assumed was coming his way, then heard gunfire and felt bullets hitting his car. “I’m looking at the people in my car, and they looking at me, and we all feel like we’re about to die,” Washington recalls.

When Washington looked up, he says, he saw three police officers pointing their guns at him. Another officer pulled Greene from the back seat by his dreadlocks and threw him to the ground. Washington got out and saw the parking lot filled with unmarked police cars. “It’s looking like a movie scene,” he says. The officers cuffed Washington, sat him on the curb, and then tore the speakers out of his car. “I’m looking at my brother like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Things clicked into place for Washington: The van driver who stared him down when he picked up Greene, the feeling that they were being followed, picking up Williams in a grocery parking lot — Williams had set them up.

Washington was taken to a satellite RPD facility in Northeast Raleigh where, he says, he was strip-searched and interrogated. There, he met Abdullah. The officer’s eyes were piercing and shaky. “He kind of looked like a drug addict,” Washington says. “I’m just looking like, ‘What’s wrong with this dude?’” Washington was charged in Wake County court with trafficking heroin and conspiracy to traffic heroin, and he spent six days in jail before posting bond with the help of friends and family. But the charges remained.

“It brought me to tears, man, because I thought my life was over. I thought I was really about to be guilty for something that I don’t even know what I did.”

Blake Banks, alleged Abdullah victim

As Washington’s case made its way through the court system, Greene’s case was on a different and far more consequential track. He was a convicted felon, and the officers had found a gun on him, which exacerbated his trafficking charge. His case was given to then-Wake County assistant public defender Jackie -Willingham. She asked Greene if he was selling heroin — there were plea deals available for people who cooperate with law enforcement. He told her he was innocent.

Willingham was given two more Abdullah cases based on evidence provided by Williams. Both clients maintained their innocence and said they didn’t know where the heroin found on them had come from. Willingham notified an assistant district attorney with the Wake County DA’s office that something seemed off about her three cases — they were Black men arrested by Abdullah, and their stories were oddly similar.

Willingham also looked up other Abdullah cases and called the defense attorneys assigned to them. They said their clients had all told them the same story: They didn’t touch heroin. Willingham emailed a Wake County ADA about the irregularities. The ADA emailed her back, insisting that her clients were all part of the same “Blood set,” meaning they were in the same gang. Not satisfied, Willingham asked a private investigator in the public defender’s office, who is a former RPD Vice member, to look into her clients. The PI pulled reports, cross-referenced databases, and made some calls. He couldn’t identify any current gang affiliation with the men.

On June 5, 2020, the lab results on the substance found in Greene’s case, which Adbullah had claimed was heroin, came back negative for drugs. A couple of weeks later, Willingham got an email from an ADA who questioned the videos submitted as evidence for the drug purchases. By June 30, the DA’s office was dismissing Willingham’s Abdullah cases and a dozen others, often because the informant — Williams — was deemed unreliable.

Though her cases were over, Willingham wanted to warn other defense attorneys to be on the lookout for cases with Abdullah’s name attached, and she wanted a notice appended to his file. So that July, she wrote a letter to the RPD and Wake County DA’s office saying she was bothered by what she had uncovered, and that “there are more cases that need to be investigated.”

That September, Abdullah was placed on administrative leave. The North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation also launched an independent review of his cases a month later.

As investigations brewed behind the scenes, the men who’d allegedly been framed began to coalesce and look for accountability.

Shortly after the cases were dismissed in the summer of 2020, Washington reached out to a friend of his named Blake Banks, who had also been arrested by Abdullah, to see if he might be interested in filing a lawsuit.

Banks, who’d gone to high school with Williams, had been in and out of jail and prison, mostly for crimes related to selling weed. The men ran into each other once while incarcerated, but otherwise hadn’t been in touch. After Banks was paroled on a gun charge in November 2018, he worked hard to rebuild his life. He got two jobs after he was released from prison, then moved on to construction, and finally transitioned to freight-truck hauling.

About a year after he was released from prison, Banks says, Williams hit him up on Facebook and asked where he could buy heroin. Banks told Williams he didn’t get down with people like that, adding in a polite brushoff that he would see what he could do. But Williams kept texting about drugs, Banks says. One time, Williams said he was at the spot where they agreed to do a buy. “I said, ‘Bro, I never said that I had anything for you,’ ” Banks remembers. Eventually, Banks stopped responding to Williams’ messages.

On a late-December morning in 2019, after driving with his godmother to drop off her daughter at work, their car was swarmed by the RPD. Officers pulled Banks from the car, and handcuffed him in front of his family.

“It brought me to tears, man, because I thought my life was over,” Banks says. “I thought I was really about to be guilty for something that I don’t even know what I did.”

According to Abdullah’s incident reports, Banks had set up a heroin buy with informant Williams on Nov. 26, 2019. Abdullah wrote that on Dec. 11, 2019, he also watched Banks and another man sell heroin to Williams.

When Abdullah moved in for the arrest that day with other officers, he claimed, Banks sped off in a red Dodge Charger, and the other man simply ran away.

But Banks didn’t arrange a drug buy on Dec. 11; his receipts show he was out of the state on a truck delivery. And as for the supposed sale that occurred in November, lab tests came back negative for drugs.

Banks was able to post bond with the help of family, but his relationships with them were strained. His mom thought he was back to selling; his girlfriend broke up with him. And social media was hell — his mug shot was everywhere.

For Washington’s part, with the bond and legal fees resulting from his case, he owed more than $22,000 in court debt. Over the next year, he worked up to 12 hours a day between construction and driving for Lyft to dig himself out of debt.

He still suffers from intense anxiety from that day his car was shot in the supermarket parking lot with what he later learned were rubber bullets. And he’s never sure what might set him off.

“I could be parked somewhere and it could be dark outside and I’ll think about it,” he says. “I remember the shots, how I felt at that moment.

“Bro, I don’t know if you ever felt like you was about to die. That’s a feeling you’ll never forget.”

Once Willingham’s Abdullah cases were dismissed, she referred those clients to Abraham Rubert-Schewel, a civil rights attorney in Durham who got his start clerking for Jack Weinstein, then the last living member of Thurgood Marshall’s legal team that prepared Brown v. Board of Education.

After he gathered five plaintiffs who said they were framed by Abdullah, Rubert-Schewel reviewed the state’s investigation into the detective.

“It was all these people who had had large parts of their lives taken away by blatant, clear misconduct, and it was kept away in this secret file where no one could really know about it,” Rubert-Schewel says.

Through depositions and discovery, he says he confirmed that at least six other officers knew that Abdullah’s arrests were bogus — but didn’t stop him. Abdullah’s supervising sergeant, William Rolfe, provided little oversight, according to the federal civil rights lawsuits. In his deposition, Rolfe said he routinely broke with written RPD oversight policies for supervisors because that was the norm. “It was just status quo,” he said in a deposition. “[T]here was nobody around saying, ‘This is OK, that’s OK.’ You just do it. You’ve learned to do from your predecessors.”

Four other officers told Abdullah that the heroin Williams turned in looked like brown sugar. And the lawsuits and depositions indicate they allowed arrests to occur after field tests came back negative. In a text thread among the officers, they joked about taking “ ‘bets’ on whether Aspirin would again produce ‘fake heroin,’ ” according to a recent court filing. One of the officers did report Abdullah’s pattern of false arrests to Rolfe and a supervising lieutenant. He stated in his deposition that he believed no action was taken because Abdullah is Muslim and Black, and the supervisors were afraid of being called out for discrimination. (The officers named in the lawsuits deny the allegations against them.)

Based on all the facts he had gathered, Rubert-Schewel filed a suit on April 26, 2021, on behalf of 12 people who were swept up in Abdullah’s cases, including Washington and Banks. And five months later, the city reached a $2 million settlement with the plaintiffs. Williams was indicted by the Wake County DA on five counts of obstruction of justice.

That September, Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman told The Assembly, a local news outlet: “We do not have evidence of criminal wrongdoing by Officer Abdullah or others with the Raleigh Police Department.” The RPD fired Abdullah in October 2021, more than a year after his scandal broke.

“You got pictures, you got videos, look at ’em and make sure you’re doing the right thing. They’re getting paid by our tax money. I’m paying their salary.”

Amir Abboud, alleged Abdullah victim

At this point, word was out that Rubert-Schewel could get results. And people who had given up on accountability from the RPD were reaching out.

People like the sister of David Weaver, who told Rubert-Schewel that her brother was wrongfully convicted on cocaine-trafficking charges by Abdullah and was serving time in prison. On Aug. 23, 2018, Abdullah had pulled Weaver in for selling nearly three grams of crack cocaine — then tried to flip him to become an informant, according to Weaver’s lawsuit. Weaver didn’t budge, and Abdullah strip-searched him and went through his clothes with another officer. Abdullah turned his back on Weaver and then produced a brown paper towel that contained 36 grams of crack cocaine, roughly the equivalent of 120 large crack rocks. Abdullah claimed in his incident report that he’d found it “tucked inside the subject’s underwear.” Weaver spent 16 months in pretrial jail and ran through multiple lawyers while maintaining his innocence. He eventually accepted a plea deal from prosecutors and was sentenced to 35-to-51 months in prison.

Rubert-Schewel was also connected with Yolanda Irving and Kenya Walton. He showed them the body-cam footage from the raid on their apartments as he built the case. Both women were overwhelmed when they saw the scene from the officers’ perspective. “It was so disgusting to see five to six police officers chasing my 12-year-old down, like he was a dog,” Irving says.

But Irving wasn’t the only person who’d said she had her home breached by the RPD based on faulty evidence. Kesha Knight, now 43, has been disabled since 2011 from multiple strokes and needs a cane or walker for mobility. Her federal civil rights complaint states that on Feb. 12, 2020, she had just gotten out of the shower in her apartment in Northeast Raleigh and was wearing only pajama bottoms and a bra when SEU officers broke into her home. She was later hospitalized with chest pains and anxiety from the incident, and currently suffers from PTSD.

On April 7, 2021, Amir Abboud was at home in the East Raleigh suburbs when video from a home-security camera shows the RPD breaking through his door on a joint narcotics raid with the State Bureau of Investigation. All they found in his home was Abboud’s then-pregnant wife and 11-month-old son playing on the living room floor. The boy cried when he saw the RPD point their rifles at him and his mother. After the officers seemed to realize they had the wrong person, they packed up their gear and left, Abboud said.

“You got pictures, you got videos, look at ’em and make sure you’re doing the right thing,” Abboud says. “They’re getting paid by our tax money. I’m paying their salary.”

The State Bureau of Investigation and RPD have denied wrongdoing in the incident. Abboud reached out to lawyers in hopes of being compensated, but no one wanted to take his case. He said he was told he’d spend more money fighting it than he would get in a settlement. He had given up on getting accountability until he saw details of Irving’s home invasion while scrolling through YouTube at work.

Public records obtained by Rubert-Schewel show that the RPD Drugs and Vice Unit executed 438 search warrants between 2018 and 2021. A review of North Carolina search-warrant practices done by law professor Jeffrey Welty out of the University of North Carolina found that quick-knock warrants — warrants where officers announce themselves then break down the door, similar to no-knock warrants — seem to be standard practice in narcotics cases in North Carolina.

In February 2022, Rubert-Schewel, with his firm the Tin Fulton Walker & Owen Law Offices, and attorneys from Emancipate NC, a local legal-support and civil rights nonprofit, filed a lawsuit on behalf of Irving and Walton against the city of Raleigh, Abdullah, and the implicated officers. Weaver was released from prison in March 2022; his civil rights complaint was filed that June. Knight’s complaint was filed against the city of Raleigh and the officer who obtained the warrant in her case, on Nov. 30, 2022. Abboud’s claim against the State Bureau of Investigation was filed in February. Irving and Walton’s lawsuit has yet to reach a settlement and is on track for a trial.

The city of Raleigh, the Raleigh Police Department, the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigations, and the North Carolina Department of Justice declined to comment for this story, and District Attorney Lorrin Freeman did not respond to multiple calls, voicemails, and emails.

More than two years after former public defender Jackie Willingham wrote her complaint about Omar Abdullah, the former officer was indicted in July 2022 by the Wake County district attorney’s office on just one count of obstruction of justice. The indictment stems from the May 21, 2020, raids on Irving, Walton, and Vanirvin’s apartments.

Prosecutors allege that in the Vanirvin case, Abdullah provided false statements and “falsely represented” the substance in the controlled buy leading up to the arrest. “This offense was infamous, was committed with secrecy and malice, and was done with deceit and intent to defraud,” according to the indictment. Attorneys for Abdullah and Williams did not respond to requests for comment.

Abdullah turned himself in days after the indictment. He’s pleaded not guilty to the charge. “He plans on vigorously defending himself in the criminal action,” his defense lawyer Christian Dysart wrote in a recent court filing. In a March 16 filing in one of the civil rights lawsuits against Abdullah, his attorney wrote that “Abdullah expressly denies any allegation that he fabricated evidence.” Williams has also pleaded not guilty to his charges.

This alleged deception wasn’t even the impetus for stopping the scheme, in Rubert-Schewel’s view. Rather, it was the apparent theft of some of the cash used in the controlled buy. Rubert-Schewel says $800 was given to Williams to buy heroin from Vanirvin, but only $60 was recovered by the RPD. “They knew what was happening, and they knew that the informant was producing fake heroin,” he says of Abdullah’s RPD Vice team. He laments that nearly two dozen Black people were wrongfully imprisoned, people lost jobs, parents were separated from their children, relationships were destroyed, but “no one stopped it until [Williams] stole buy money.” He believes there’s a good chance most of the false-arrest cases involving Abdullah and Williams have been found, but for cases where Abdullah performed his police work without Williams, there may be dozens more that could be dismissed.

Advocates say that Wake County DA Freeman should follow the lead of the Shelby County DA in Tennessee, who is set to review all the cases involving the officers who were involved in Tyre Nichols’ death. “I think it’s clear to see that there is a distinctly different way that Freeman and the Wake County’s District Attorney’s Office handles interactions with law enforcement,” instead of following the “gold standard” laid out in Memphis, says Dawn Blagrove, executive director and attorney at Emancipate NC.

Christy Lopez, a former head of civil rights litigation in the U.S. Department of Justice, who has investigated numerous police departments, including the Ferguson Police Department after the killing of Michael Brown Jr., says every case connected to Abdullah should be investigated.

“These are people’s lives. They’re in jail, they have criminal records because of, potentially, this guy lying. It should go back as far as the guy’s been on the force,” she says. “If you want to do justice, you have to be aggressive about it. You have to send a strong message: This is intolerable.”

Howard Jordan, a former Oakland police chief who was an expert consultant on Rubert-Schewel’s first lawsuit, believed Abdullah suffered from “hero-cop syndrome” and cut corners to make arrests. “They’re in a position where they’re rewarded for it,” Rubert-Schewel says. “You add all that up and it creates kind of this toxic environment where, who cares if you get the wrong person’s house on a raid? Who cares if you arrest a weed dealer for heroin trafficking? Because at the end of the day you got somebody off the street who probably was bad anyways.” He gives a melancholic laugh at the absurdity of it and says, “It just so happened that they were wrong about it all.”