Here We Go Again

The short history and long tail of “zero tolerance” policing in Baltimore.

This article was produced in partnership with The Baltimore Beat, The Google News Initiative's Data-Driven Reporting Project, and The Real News.

It was about to get dark.

In the summer of 2003, Devin was 19 years old and living in West Baltimore with his mom and two brothers, just a few blocks away from the Western District Baltimore Police station. Every night around 9 or 10 p.m., Baltimore cops patrolled the area heavily. They drove in marked and unmarked cop cars searching for signs of disorder, ready to round up people for mass arrest. It was all part of a policing strategy introduced in the late ’90s called “zero tolerance.”

“It always happened around sundown,” Devin told The Real News. “The police see you out with even just one or two people and they just looked at you and you knew they were gonna wild out.”

One night, Devin and his older brother were on their stoop, arguing. “Brother argument type shit,” Devin explained. Then, an unmarked cop car drove the wrong way up their one-way street and pulled in front of them.

Officers jumped out. They grabbed Devin’s brother and slammed him against their car. They put Devin in a chokehold and threw him to the ground. A neighbor sitting on their stoop was rounded up just for being nearby. Devin and his older brother were in handcuffs and the whole block was outside, including Devin’s mom. “They’re not doing anything,” she told the officers from the stoop. “They were just talking.”

Police ordered everybody back inside. Devin’s mother called a family friend. Her sons were about to go to jail and she was going to need help getting them out. Officers who saw Devin’s mom on the phone inside broke down the door, terrifying his youngest brother. “My brother has autism and there’s cops in the house,” Devin said. “It was madness.”

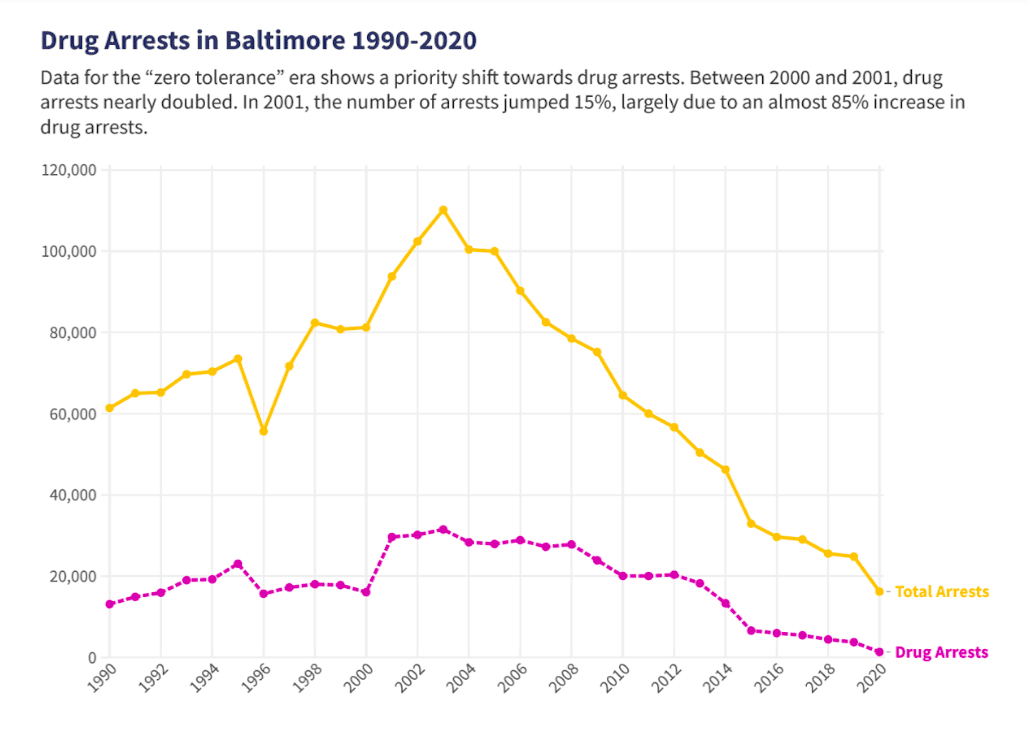

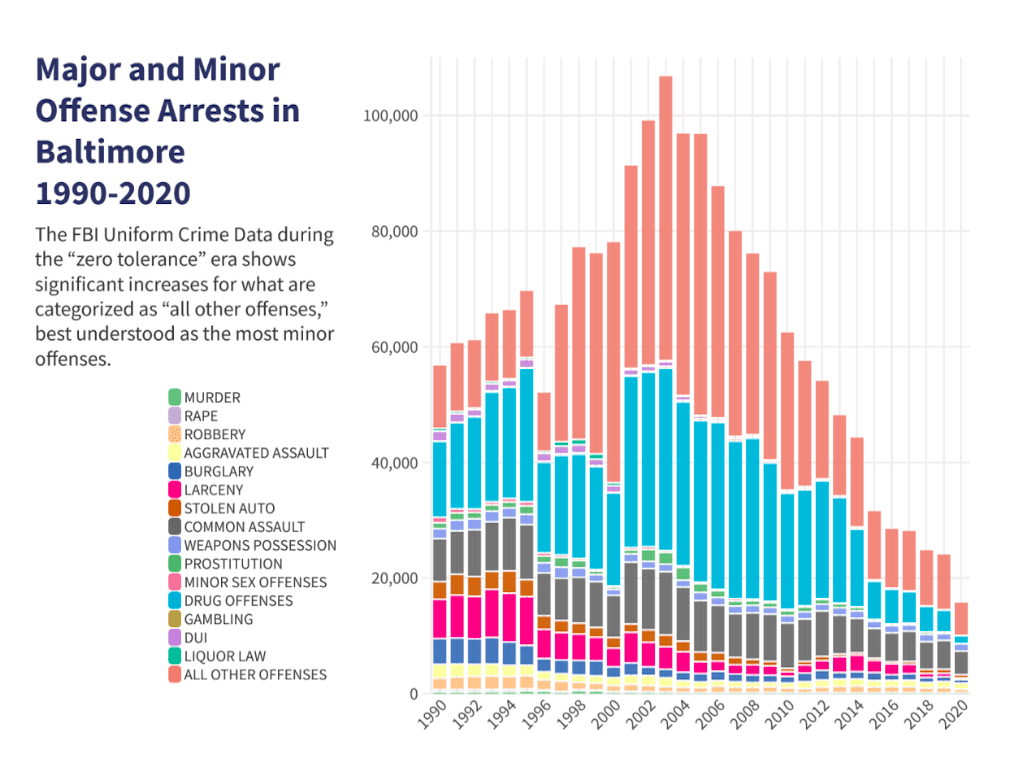

Devin’s experience was not unusual in Baltimore under zero tolerance, a policy enacted by Martin O’Malley, who served as the city’s mayor from 1999 to 2007. The policy was based on the New York Police Department’s “broken windows” approach to crime, which encouraged police to make arrests for smaller infractions. Broken windows proponents argued that a police department that did not engage in drastically reducing low-level offense ceded cities to disorder leading to more, sometimes serious, crime.

Devin’s mom wasn’t taken away in handcuffs that night but she was left with a front door off its hinges, her middle and oldest children in jail, and her youngest terrified.

Devin and his older brother sat in Central Booking for nearly a day. Then, without ever seeing any charging documents, they were released. “No papers—nothing. After 19 hours, they let us go,” Devin said. “And my mom paid for our broken door. We didn’t have the money to keep fighting that shit in court.”

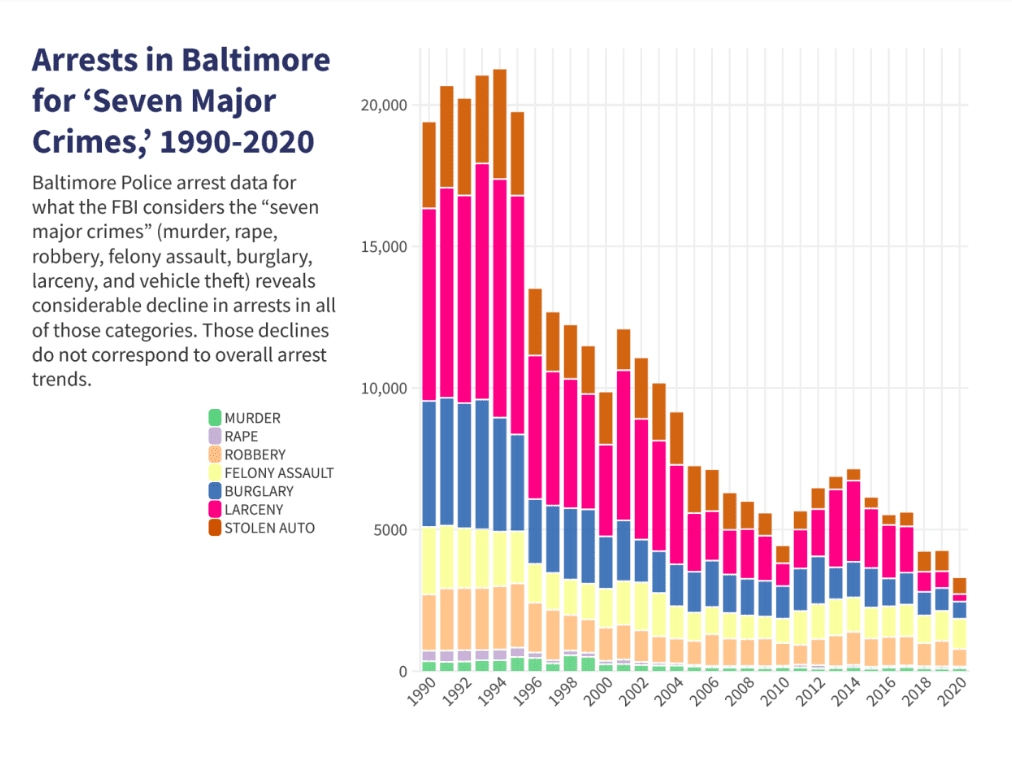

In the early 2000s, the city’s political and law enforcement establishments credited slight declines in violence to increased arrest policies under zero tolerance. But zero tolerance did not substantively reduce crime. Especially when accounting for the city’s population decline, its reductions were even less significant than police and politicians claimed.

State Senator Jill Carter told The Real News that zero tolerance further frayed the relationship between police and communities. “Zero tolerance had a direct effect on the destabilization of the Black family in poor neighborhoods that is still present to this day,” Carter said.

Breaking Balls, Broken Windows

In a 1982 article in The Atlantic, “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety,” political scientist James Wilson and criminologist George Kelling presented the “broken windows” theory of crime reduction: increasing arrests for low-level crimes, the theory argued, reduces the likelihood of more serious crimes occurring. “Many citizens, of course, are primarily frightened by crime, especially crime involving a sudden, violent attack by a stranger. This risk is very real, in Newark as in many large cities,” Wilson and Kelling wrote. “But we tend to overlook another source of fear—the fear of being bothered by disorderly people. Not violent people, nor, necessarily, criminals, but disreputable or obstreperous or unpredictable people: panhandlers, drunks, addicts, rowdy teenagers, prostitutes, loiterers, the mentally disturbed.”

Broken windows effectively gussied up a standard police tactic of stopping and harassing people like “rowdy teenagers” to make them feel unwelcome and get them off the street. Jack Maple, a lieutenant for the New York Transit Authority in the ’80s, later wrote in his memoir that broken windows was “merely an extension of what [cops] used to call the ‘breaking balls’ theory.”

Maple had been breaking balls for years. As a subway cop, he mapped where crime occurred— he called the maps “charts of the future”—and sent officers to those areas in order to make the police presence known, and to intimidate and clear out those deemed undesirable. Maple and others claimed “breaking balls” in the subways had reduced crime, especially robberies.

In 1994, under newly-elected Mayor Rudy Giuliani, broken windows went above ground and citywide. Giuliani made Maple an NYPD deputy commissioner and William Bratton, the New York Transit Authority commander, the new police commissioner. “We are going to flush [homeless people] off the street in the same successful manner in which we flushed them out of the subway system,” Bratton said. More importantly, Maple’s “breaking balls” was given a technocratic sheen. They called their crime fighting program COMPSTAT (short for “computer statistics”). The computerization and quantification program made it much easier for crime statistics to be closely reviewed and calculated. Paired with broken windows, the focus on week-to-week statistics emboldened officers to make an increasing number of arrests.

“Broken windows” boosters argued that, after the policy was enacted, crime in New York City decreased. From 1993 to 1994 (Giuliani’s first year in office) the number of murders declined from 1,946 to 1,561. But homicides were already on the decline before broken windows—and before Giuliani’s tenure as mayor. New York City’s homicide rate peaked in 1990 at 2,245 murders, and after that began its drastic decline under Mayor David Dinkins, Giuliani’s predecessor and a broken windows skeptic.

“The amazing facts of New York City’s crime decline have been condensed into a sound bite in which a heroic mayor and aggressive police created a zero tolerance law enforcement regime that drove crime rates down in the 1990s,” criminologist Franklin Zimring wrote in his book The City That Became Safe. “Close scrutiny of the data reveals this popular fable to be almost equal parts truth and fantasy.”

Nevertheless, Giuliani and his police department credited broken windows with the city’s historic drop in crime. Soon, Maple, along with Bratton aide John Linder, started a consulting firm where they took COMPSTAT and broken windows to other cities. In 1996, New Orleans hired Maple and Linder to show the New Orleans Police Department how to “go get the scumbags.”

At the same time, Baltimore City Councilperson Martin O’Malley and City Council President Lawrence Bell argued that Baltimore needed to study New York’s success in crime fighting. The duo criticized Mayor Kurt Schmoke and Baltimore Police Commissioner Thomas Frazier for the city’s high levels of violence. In 1990, Baltimore City surpassed 300 homicides for the first time and stayed above that number for years.

In August 1996, Baltimore City Council’s Legislative Investigations Committee took a trip to New York where they witnessed broken windows-style policing in action. Soon, the committee issued a report, “The Success of New York City’s Quality of Life/Zero Tolerance Policing Strategy,” which, as its title suggests, argued for broken windows-style policing in Baltimore.

Schmoke and Frazier opposed the idea. They argued that Baltimore courts couldn’t handle an increase in people coming through the system, and that the approach encouraged officers to make questionable arrests. But after O’Malley’s fact-finding mission, they began to reconsider.

In October 1996, three Baltimore police districts enacted a “limited citation experiment” in which several offenses (open container, littering, disorderly conduct) were prioritized by officers who began handing out citations that brought small fines and possible jail time.

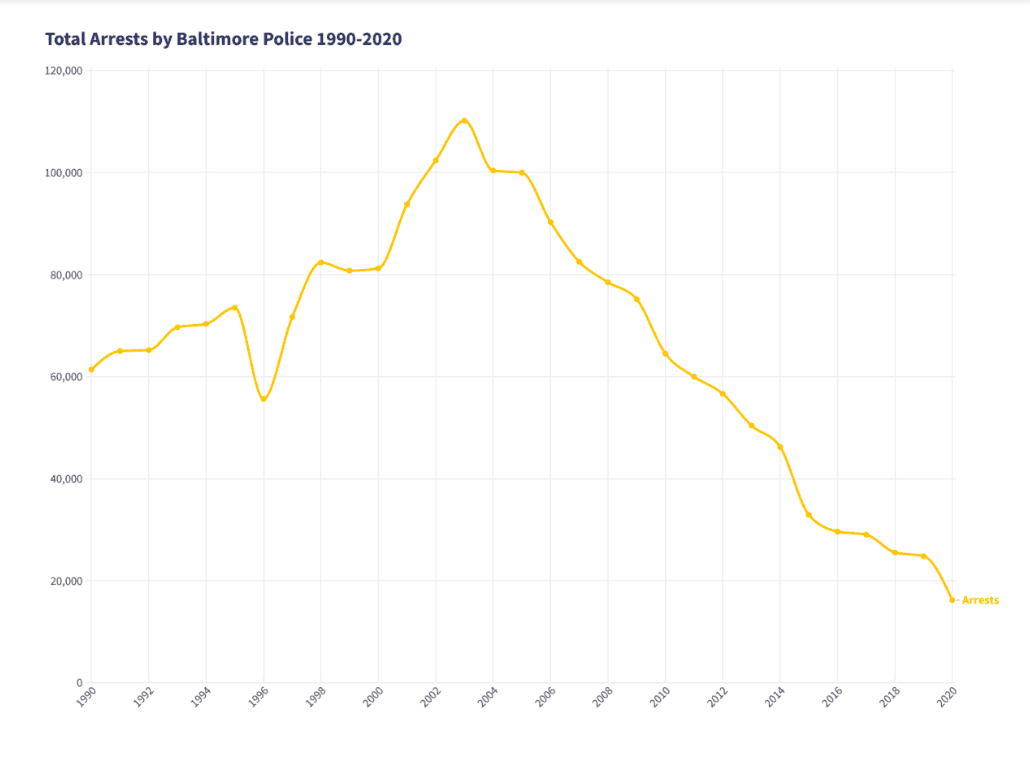

Arrests increased. In 1996, Baltimore Police made 55,662 arrests. In 1997, there were 71,709 arrests; in 1998, 82,377; and in 1999, 80,775.

In 1999, Schmoke announced he was not going to run for a third term as mayor. A dozen-plus Democratic candidates entered the mayor’s race, including Bell and O’Malley. O’Malley’s 1999 campaign literature argued that “the use of citations,which make fewer arrests necessary,” would make Baltimore less violent and its jails less full. He argued “fewer people may actually be locked up using quality-of-life policing strategies.”

What actually transpired under O’Malley was an experiment in mass incarceration that, by the time Devin and his brother were stopped by police in front of their homes in 2003, resulted in over 100,000 arrests a year in a majority-Black city of only 630,000 people.

“O’Malley Is A Killer”

In November 1999, O’Malley was elected mayor. After winning the Democratic primary with 53% of the vote, he took 90% of the general election vote. In his inauguration speech, O’Malley avoided tough-on-crime rhetoric and instead promised “a future where justice is not a dream deferred, but a goal achieved.” He declared Baltimore “the greatest city in America.” He then put the slogan on benches across the city.

But as arrests increased under O’Malley, police violence escalated. In February 2000, Ralph Chambers was chased and then shot by police after he was spotted dealing drugs. Chambers, who was unarmed, died. His brother Paul connected zero tolerance policing to the killing. “O’Malley made it clear it was not going to happen like this,” Chambers told The Baltimore Sun. “They don’t have to kill them to get them off the corner.”

At the scene of the shooting, protesters chanted, “O’Malley is a killer.”

Broken windows policing in New York was yielding similar problems. While crime continued to decline, between 1993 and 1995 complaints of illegal search increased by 135%, excessive force complaints against police increased by 61%, and abuse of authority by 86%. NYPD brutality became national news. In 1997, NYPD officers arrested Abner Louima, punched him, beat him with a police radio, and then, at the precinct, stripped him and sodomized him with a plunger. Justin Volpe, the officer who assaulted Louima, was indicted in federal court and sentenced to 30 years in prison. Prosecutors called the attack “one of the most heinous crimes in New York City’s history” (Volpe was released from federal prison in June 2023 after serving 24 years of his sentence).

In 1999, the NYPD killed Amadou Diallo, shooting at him 41 times, hitting him 19 times. The four officers charged in the Diallo shooting were acquitted in federal court in 2000. “Sure, crime is down. There wasn’t much crime in the Soviet Union, either,” one protester said. “Unfortunately, our mayor has reinforced the attitude that police can do whatever they want to young Black males as long as the crime rate goes down.” Even after Diallo and Louima, the police remained so emboldened under Giuliani—and unaccustomed to any criticism of their broken windows tactics—that they staged angry protests over the release of Bruce Springsteen’s song about Diallo, “American Skin (41 Shots).” At Springsteen concerts, they heckled him, pulled a police escort for one of his major shows, and a Fraternal Order of Police official called Springsteen “a floating fag.”

Nevertheless, O’Malley courted the NYPD brains behind broken windows. Maple and Linder’s consulting firm came to Baltimore to review the police department. They found that it was “dysfunctional” and “to no small degree corrupt.” Maple and Linder said the department and the city’s crime problem could be fixed by instituting COMPSTAT and zero tolerance policing. O’Malley agreed.

In 2000, O’Malley imported more New York City cops. Ed Norris, who helped implement COMPSTAT and broken windows in New York, became the next police commissioner of Baltimore City. Norris replaced Ron Daniel, whom O’Malley and others perceived as insufficiently supportive of zero tolerance. Daniel had replaced Thomas Frazier, who was also critical of zero tolerance.

In 2001, both the number of arrests and murders in Baltimore were high: there were 256 murders, 684 nonfatal shootings, and 93,778 arrests. The homicide clearance rate, meanwhile, began to decrease. In 2000, it was 77.8%, and in 2001, 66%—a sign that the single-minded focus on low-level arrests was a distraction from addressing much more serious crime.

In 2002, former NYPD commander Kevin Clark replaced Norris, who went to work for the Maryland State Police (in 2003, Norris was federally indicted for using police money for personal matters and was sentenced the next year to six months in federal prison). In 2001, three years and four police commissioners into the O’Malley administration, the murder rate had slightly declined from 46.9 murders per 100,000 people in 1999 to 38.7 murders per 100,000.

That decline put the murder rate back to where it was in the early ’90s, when O’Malley criticized Schmoke. In 1991, there were 304 murders and a murder rate of 40.4 per 100,000.

O’Malley and his NYPD consultants promised that the homicide number would drop to 175 by 2002. O’Malley believed that getting there required increases in arrests—and some good PR.

NYPD consultant Linder created Baltimore’s “BELIEVE” campaign, funded with $2 million from the Baltimore Police Foundation. Those words in white on a black background showed up on billboards all over the city. O’Malley called the campaign “spiritual warfare.” The slogan promised positivity and a sense of a better future at a moment when the promises of zero tolerance had failed to materialize—and police were increasingly out of control.

The peak of zero tolerance was 2003. That year, there were 110,164 recorded arrests in Baltimore, along with 20,000 more people who, like Devin and his brother, were released without charges—but not before spending time in jail. Those who weren’t part of this “catch and release” form of enforcement went through a criminal legal system clogged by the high numbers of arrests, waiting for weeks or even months to see a judge. “They actually had police supervisors stationed with printed forms at the city jail—forms that said, essentially, you can go home now if you sign away any liability the city has for false arrest, or you can not sign the form and spend the weekend in jail until you see a court commissioner,” Baltimore reporter and The Wire showrunner David Simon said in a 2015 interview. “And tens of thousands of people signed that form.”

Carter, now a state senator, was then a ṡtate delegate, and criticized O’Malley’s zero tolerance strategy. “There were hundreds of thousands of arrests throughout O’Malley’s term as mayor. And one third to one half of those were illegal,” Carter said. “Either they were arrests without charges—because there was no probable cause—or they were ‘abated by arrest’ because after they took the person to jail, they were held in Central Booking for months before the court date.”

“Stop The Illegal Arrests”

In 2004, O’Malley was reelected, in part due to the city’s modest reductions to violence. That year there were 276 murders with a murder rate of 43.5 people per 100,000. Arrests were soaring: there were 100,388 arrests in 2004. One person out of every five arrested were released without being charged.

Concerns from Carter and others about zero tolerance and mass arrests grew too large for the city’s leadership to ignore. Defense attorney Warren Brown was often spotted in West Baltimore by commuters holding a sign that said, “Mr. Mayor, Stop the Illegal Arrests.” In 2005, there were 99,980 arrests, and in 2006, there were 90,823.

In 2006, the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland and the Baltimore chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sued the city and the police over unconstitutional arrests. “The Baltimore City Police Department rewards police officers with more arrests and punishes officers with fewer arrests, regardless of the number or success of resulting prosecutions,” the ACLU said in June 2006. “As a consequence, Baltimore prosecutors decided to drop the charges against approximately 30 percent of those arrested without a warrant in 2005 prior to any involvement by a defense attorney.”

Zero tolerance effectively ended in 2007, not long after the ACLU/NAACP lawsuit against the BPD (the plaintiffs in the ACLU lawsuit were later awarded $870,000).

Meanwhile, O’Malley ran for governor of Maryland and won. New Mayor Sheila Dixon and her Police Commissioner Frederick Bealefeld sought to reduce violence—and arrests. Between 2007 and 2011, murders and nonfatal shootings steadily declined. Murders and nonfatal shootings declined from 282 murders and 636 nonfatal shootings in 2007 to 223 murders and 419 nonfatal shootings in 2010. Arrests also declined. In 2007, there were 82,529 total arrests, and by 2010, 64,524 total arrests. Dixon and Bealefield attributed the success to a focus on people who committed violent crime.

This was more than a continuation of the slight decline under zero tolerance: it was the most significant decrease the city had seen in decades. It was a rare moment of stability in the police department. Bealefeld was the first commissioner to last more than three years since Frazier, four commissioners earlier. But City Hall was in turmoil. Mayor Sheila Dixon was federally charged with corruption and served a year under indictment before pleading guilty and stepping down in early 2010. She was replaced by then-City Council President Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

Despite the chaos in City Hall, Baltimore chipped away at the staggering arrest numbers from O’Malley’s time in office, and at the same time decreased violence.

In 2011, Baltimore City recorded only 196 murders with 60,008 arrests, removing Baltimore, at last, from the list of top five deadliest cities in the United States. It was also the first time the homicide number dropped below 200 since 1978. The murder rate declined to 31.3 per 100,000 people, putting the city back where it was in the late ’80s (in 1989, there were 259 homicides, with a murder rate of 33.9).

“Widespread Community Disillusionment”

For Governor O’Malley, 196 murders in Baltimore in 2011 during a period of decreased arrests was evidence that zero tolerance worked. Its effects just took a little longer, O’Malley suggested.

“To see that 175 mark on the horizon, to think of all the moms and all the dads that aren’t going to be standing by graves of their kids, I don’t think there’s anything about which I will ever be more grateful in public service, and I’m not going to quibble with God over the timing,” O’Malley said.

O’Malley’s celebration of Baltimore’s 2011 murder rate did not acknowledge the many more moms and dads whose kids were locked up. The amount of jobs and housing lost as a result of an arrest, or lost because that arrest precluded housing and employment opportunities in perpetuity, seemed to not matter to the city’s leadership—and has never been quantified.

“People were arrested. They were held in Central Booking for months before the court date. That was why it was so devastating,” Carter said. “You’re in there for two months, and then you get released—because it’s either without charges, or abated by arrest because the charge was something like trespass. You were working, you had an apartment. Now you lost both your house and your job.”

“The city made about a hundred thousand arrests. Now, some of them were the same people over and over again, but think about that: 100,000 adult arrests in a city of [600,000] people,” former Police Commissioner Bealefeld said. “It’s incredible. And it didn’t move the needle.”

For Bealefeld, strategic, targeted policing was how murders and shootings were reduced. Under Bealefeld, the police department’s targeting of violent offenders relied on aggressive, specialized units in plainclothes—called “knockers” on the street. The since-disgraced Gun Trace Task Force was formed in 2007. The killings of Anthony Anderson in 2011 and Tyrone West in 2013 were by Baltimore’s “knockers.”

O’Malley spent his final years as governor telling Rawlings-Blake to increase arrests because the homicide numbers for 2012 (218), 2013 (233), and 2014 (211) were higher than the 2011 low point.

In 2015, O’Malley ran for president. He announced in late May of 2015, amid the headiest days of the Black Lives Matter movement; Mike Brown was fatally shot by police in Ferguson in 2014, and Freddie Gray was killed by police in Baltimore in April 2015.

During O’Malley’s speech announcing his presidential run, he called the Baltimore Uprising a “scourge of hopelessness that happened to ignite” when it did. He stressed that hopelessness “transcends race.” Activists protested O’Malley’s announcement, complete with a “die-in” to represent the harms of the zero tolerance era. In a moment of widespread insurrectionary rage at cops and calls for police reform from elected officials, O’Malley struggled to defend zero tolerance and was swamped with negative press about the policy.

In a widely read April 2015 interview, Simon blasted O’Malley and the zero tolerance era. “The department began sweeping the streets of the inner city, taking bodies on ridiculous [misdemeanor charges], mass arrests, sending thousands of people to city jail, hundreds every night, thousands in a month,” Simon said. Support from centrist pundits like Matthew Yglesias did little to boost O’Malley’s flagging campaign: In February 2016, he suspended his campaign after receiving just 0.54% of the vote in the Iowa caucus.

That same year, the US Department Of Justice’s Civil Rights Division issued a report on the Baltimore Police that blamed zero tolerance for the divisions between residents and the police. “The Department’s current relationship with certain Baltimore communities is broken… This fractured relationship exists in part because of the Department’s legacy of zero tolerance enforcement,” the report said. “‘Zero tolerance’ enforcement made police interaction a daily fact of life for some Baltimore residents and provoked widespread community disillusionment with BPD.”

“Here We Go Again”

In June of this year, newly elected Baltimore City State’s Attorney Ivan Bates encouraged Baltimore officers to once again ramp up enforcement of low-level offenses. This time, officers wouldn’t make arrests for “quality of life” offenses. Instead, they would give Baltimoreans citations and have them appear before the newly-established Citation Court. There, they could face a fine or jail time—though mostly likely community service—and with it, Bates claimed, access to “wraparound services.”

A Baltimore Police department that has failed to reduce violence and regularly claims it lacks the manpower to do so is now being told to write tickets for violations such as sleeping outside or drinking beer in public.

Health Care for the Homeless CEO Kevin Lindamood told The Real News that this is the sort of policy he hoped would not return to Baltimore.

“I think it’s fair to say that we sort of brace ourselves for this type of policy to return. We’re aware that the lives of those that we’re working with are poised to become more complicated,” Lindamood said. “By virtue of living private lives in public spaces, they’re going to be collecting citations: loitering, open container, peeing in public. And we are talking about folks that don’t have stable addresses, and so they don’t get the notice, that then turns into a failure to appear, that then turns into a more serious set of escalations.”

Last year, arrests in Baltimore City increased for the first time since 2010. Politicians and police stress that current calls for increased enforcement are not the same as zero tolerance because they are not currently engaged in a mass arrest program. But these kinds of policies should not be happening at all, Peter Sabonis, co-founder of the Homeless Peoples’ Representation Project, told The Real News.

“Oh, so it’s going to be ‘a humane citation.’ You’ll go to ‘a special court,’” Sabonis said. “The whole issue with law enforcement, especially with the low-level offenses, is it brings people who are living lives that are relatively unstructured and it is imposing these deadlines, appointments, court appearances that are a challenge for those folks to make.”

At a hearing in June about a proposed $15 million increase to the Baltimore Police Department budget, City Council President Nick Mosby asked then-Baltimore City Police Commissioner Micheal Harrison about the new policy: “The idea that now we’re going after and starting to do engagement on low-level citations, how will that affect violent crime? How will that affect officer response?” Mosby said.

“This is not a strategy to reduce violent crime,” Harrison told Mosby. “This is a strategy to reduce the number of complaints for those quality of life offenses.”

According to Harrison, the policy described by the State’s Attorney’s Office as a way “to change the culture of accountability and improve safety in the City” was not about violent crime or safety at all. What had been for decades promoted as the key to all things violent crime reduction—arresting low-level offenders—now had nothing to do with violence reduction. This was simply about reducing citizen complaints.

During the first month of Citation Court in July, The Daily Record reported that nearly everyone cited was Black and the charges were what many expected: selling bottled water without a license, drug possession, open container. Some who received citations showed up in court only to be arrested for an outstanding warrant. Those who believed they were wrongly cited often realized it was easier to plead guilty to something you didn’t do and reduce the charge rather than try and fight it in court. The Daily Record noted that, at the very moment one man stood before a judge to answer for drinking in public, there were “white baseball fans openly drinking beers on Baltimore’s light rail.”

The second month of Citation Court in August was more of the same. The Baltimore Sun reported that some people cited showed up only to learn their charges had already been dropped. Those who did not show up had a warrant out for their arrest. “Only one of 16 people who had cases scheduled… showed up to court that day,” the Sun reported. “Over the three days of citation dockets in the week of Aug. 21, [judges] issued arrest warrants for offenses such as open containers, drug possession, theft, and disorderly conduct.”

The Real News’ requests to the police department and State’s Attorney’s Office for comprehensive data about citations so far have not been answered.

The policy is not substantively addressing residents’ complaints, as Harrison suggested. And it isn’t getting those who were cited the help they need, as Bates claimed: Policing of low-level offenses undermines the outreach work already being done, especially when police are stopping people, ticketing them, and sending them to court.

An outreach worker tries to build a relationship of trust where—rightly or wrongly—those in uniform (any kind of uniform) are often perceived as someone that has caused someone living on the streets trauma,” Lindamood said. “All that work to get someone to talk to us, can sometimes take months or even years—and it can take 20 seconds to completely fragment. Once that’s fragmented, it takes an awful lot of time for us to reestablish those relationships.”

Lindamood said that a man in his seventies who has used Health Care ḟor the Homeless’ resources for decades and experienced the destructive zero tolerance era responded with resignation when he heard about the return to policing low-level offenses.

“Here we go again,” he told Lindamood.

“A Grave Human Error”

At the same June hearing where Harrison was asked about citations, he, along with then-Deputy Commissioner Richard Worley, was also pressed on violence by the City Council. The clearance rate was once again low—around 40%. Just weeks before the hearing, on Memorial Day weekend, five people were shot near Lexington Market in the middle of the day, a few feet from police officers sitting in their cars.

Overall, murders and nonfatal shootings were declining, though the police command admitted that there were more people being shot in each incident. “There is one incident that made the nonfatal shooting numbers higher,” Harrison argued. “One incident where one person pulled the trigger but six people were shot. So it was one incident. We’ve had a decrease in the number of incidents. Now that does not make it less violent… but it was a decrease in the number of incidents, but more victims were shot.”

Two days later, Harrison announced he was stepping down as police commissioner. He was replaced by Worley, a Baltimore Police veteran of 25 years—nearly the entire three-decade period of police failure covered by The Real News for this project.

A week later, the Baltimore Police Department’s $15 million budget increase was approved, putting police spending at a record-breaking $594 million for the next fiscal year.

A little after midnight on July 2, 30 people were shot and two were killed in the Brooklyn Park area of South Baltimore. They were the 139th and 140th homicides of 2023.

The shooting happened at the end of Brooklyn Day, an annual Fourth of July weekend tradition in the Brooklyn Homes public housing complex that brings hundreds of attendees. There were no police present and they seemingly weren’t interested in being there—even after it was reported that some in the crowd had weapons.

Reviews of police scanner audio that night reveal that, as early as three hours before the shooting, there were reports of people armed at the party, and one cop joked that the National Guard should handle it rather than the Baltimore Police Department. An hour later there were more reports of possible violence, including claims of people fighting and shooting.

“We’re not going in that crowd,” a cop announced over the police scanner.

As of press time, there have been 255 murders in Baltimore this year. More than 100 more people have been murdered since July’s mass shooting. However, this also means Baltimore will not surpass 300 homicides in 2023 for the first time since 2014.

Keeping the homicide number under 300 has been a top priority for Baltimore Police, if not the entire city government, since around 1990. While 300 is a shocking number of murders, far too much of the city’s policy-making is centered around this threshold. Baltimore saw 305 murders in 1990, and as violence increased it became easier to focus on that number—which O’Malley did, becoming mayor and governor and, for a brief moment, a Democratic hopeful for president. In 1990, 305 murders in a city of 730,000 residents equaled a murder rate of 41.5.

There are many other significant problems that go largely unaddressed. Baltimore had over 730,000 residents in 1990, which dropped to 648,000 by 2000, and then to 583,000 by 2020. The most recent census data for the city—2022—put the city at an even further reduced 569,000. A Baltimore that shrinks by 20% should adjust its threshold for what constitutes an unacceptable number of homicides. 240 murders per year in a city of less than 570,000 is the equivalent of 300 in 1990.

The ideal number of murders, of course, is zero. And nobody would reasonably feel safer in a city that experiences 290 murders instead of 300, especially when major cities like New York have a murder rate that hovers around only 3.5 per 100,000 residents.

As long as less-than-300 murders per year is central to police and politicians’ conception of a safe Baltimore, “zero tolerance-style” approaches will always be a tempting option for city government. There can never be too many arrests—even when too many is defined as nearly one-sixth of the city’s population, as was the case during the O’Malley era.

“What I am still struggling with today, 20 years later, is that in this majority Black city—with so many intelligent, active Black people in positions of power and leadership—such a grave human rights violation occurred with no repercussions,” Carter told The Real News. “It is truly something that will never not bother me.”

The recent soft return to zero tolerance makes a cynical kind of sense. Barring the ability to actually make the city significantly safer through policing, officers can at least harass and possibly even arrest those that make people feel unsafe. The Baltimore Brew reported that at an October fundraiser Mayor Brandon Scott provided a laundry list of his crime fighting accomplishments, including the removal of squeegee workers from many Baltimore streets. “We don’t see squeegees anymore,” Scott declared.

As of November, Baltimore murders for 2023 were down 18.9% and nonfatal shootings were down 9.9% from the previous year. This has the mayor, police, and advocates taking a victory lap. But violence reductions are happening nationwide. New Orleans had more than a 20% murder reduction this year. Detroit is on track for its lowest number of homicides in more than 50 years. Baltimore’s homicide reduction puts the city at around 260 murders for 2023. With the current population of Baltimore City hovering around 565,000, the murder rate is 46 murders per 100,000 people—near where the homicide rate was in the early ’90s when O’Malley and others deemed the violence unacceptable and called for “zero tolerance.”

Two recent surveys illustrate little improvement in how Baltimoreans feel about their police department. A Consent Decree community survey report found that, “when it comes to BPD and public safety and crime, participants reported that they disagree that BPD quickly solves crimes and arrests criminals, that BPD effectively reduces crime, or that BPD has a good working relationship with the community on matters of public safety.” A Johns Hopkins University survey found that 74% of Black Baltimoreans fear the police.

“Why do we have to do this through law enforcement? If our desire is to help people, there are better structural ways to engage people,” Health Care for the Homeless’ Lindamood said. “We’re seeing the pendulum swinging back and you know, it’s frustrating. Have we learned nothing?”