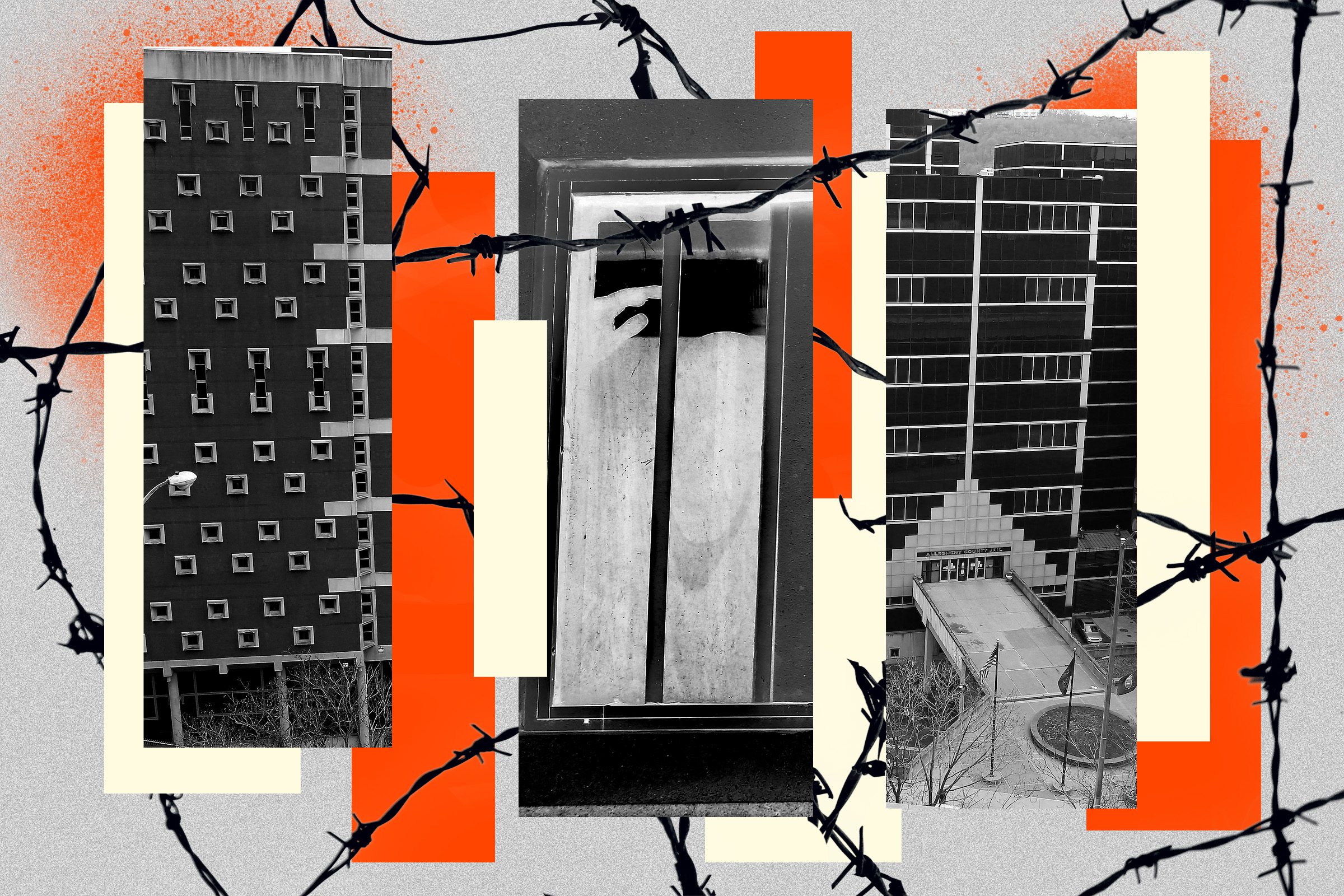

A Jail In Crisis

Deaths, Use of Solitary Soar At The Allegheny County Jail Even As Its Population Has Dropped From Pre-Pandemic Highs.

This story was produced in partnership with Black Pittsburgh and The Pittsburgh City Paper.

Gerald Thomas was depressed. It was early March 2022 and he’d been incarcerated in the Allegheny County Jail for almost a year on a probation violation. Just a few weeks earlier, his family thought he was coming home after his attorney convinced the court that the March 2021 police search of his vehicle that produced a firearm was illegal. Prosecutors dropped the charges against Thomas, but Court of Common Pleas judge Anthony Mariani wanted Thomas sent to state prison and said, “I have to put you in the cage, lasso you, corral you, stuff you, because you won’t quit.”

In mid-February, Thomas was sent back to jail after the second hearing on his probation violation. On March 6, Thomas complained of a pain in his left leg that went untreated for about a week. That day, after he ended a video call with his girlfriend who had recently given birth to his fourth child, a daughter, Thomas collapsed near his cell on the upper tier of the jail.

Several incarcerated people attempted to help Thomas after he fell down at around 12:20 p.m., according to witness interviews conducted by the Abolitionist Law Center, a Pittsburgh-based public interest law firm, and a recent National Commission on Correctional Health Care report. Jail staff sent them back to their cells and handcuffed Thomas. Someone yelled, “Medical emergency!” according to an incarcerated witness. Nurses and a medical provider rushed to his body. The medical provider slapped his face, thinking he was overdosing. Thomas was administered Narcan twice. One member of the jail staff called 911, and eventually paramedics arrived. They strapped a machine to Thomas’s chest that performed compressions. After being unconscious on the floor for over an hour, Thomas was loaded onto a gurney.

Someone picked up Thomas’s prison-issued tablet and texted his girlfriend, “Idk what’s going on with GG but he fell out about an hour ago & he was unresponsive.” The person added, “Make sure u call down here to checc [sic] the status on him or they won’t say nun [nothing].” As his body was being taken to UPMC Mercy hospital at 1:37pm, the person texted again, “Please make sure u checc [sic] on him … I hope he’s ok.”

By then, a blood clot dislodged from Thomas’s leg and was embedded in one of the arteries leading to his lungs, blocking the blood flow, causing a pulmonary embolism. Shortly after arriving at the hospital, Thomas was pronounced dead at 2:12 p.m.. He was 26 years old.

It’s unclear if Thomas’s life could have been saved, but the Mayo Clinic says prompt treatment can dramatically increase the chances of survival following a pulmonary embolism. According to the Mayo Clinic, inactivity — especially during situations where a person is in a cramped position for a prolonged period of time — can be a principal cause of life-ending clots.

According to the Allegheny County jail’s legally mandated solitary confinement reports, excluding two days in January 2022, the jail was in lockdown, when incarcerated people often spend 23 hours per day in their cells. The months before, during, and after Thomas’s death, it was the same. Including January, the jail was on lockdown for eight months in 2022.

According to a Pittsburgh City Paper, Black Pittsburgh, and Garrison Project analysis of the jail’s reports, outside of the lockdowns, in the second half of 2021 alone there were over 37,000 episodes where a person was held in a cell for a minimum of 20 hours, which amounted to over 84,500 days in solitary. Since the 2021 Allegheny County voter referendum to end solitary confinement within the jail took effect on Jan. 1, 2022, there have been 688 episodes that totaled over 1786 days in solitary. In every instance, the jail invoked “safety” as the reason for the solitary confinement. In 2022, the jail attributed its solitary confinement decisions to “medical” causes in nearly every case and also almost always invoked the COVID-19 pandemic.

Allegheny County Jail refers to solitary confinement as segregated housing, and sometimes locks two people in the same cell for over 20 hours a day for multiple days. Similar to the jail’s general population — where 66% of the people incarcerated are Black compared to a county population that’s around 13% Black — since July 1, 2021, roughly two thirds of the people held in solitary have been Black.

“The supervising staff–whoever is reading this, I want you to lock yourself or imagine being locked in your bathroom for 23 hours,” wrote a respondent to a 2021 jail survey by the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work.

“I been locked in my cell with no running water for 36 hours. Having to use the restroom on top of another man’s waste is humiliating,” wrote another respondent to a 2022 survey conducted by the Pennsylvania Prison Society.

Experts say the continued use of solitary on individuals and on the entire jail through lockdowns contradict the will of the county’s voters who overwhelmingly supported the 2021 measure to end solitary confinement.

“Nobody’s enforcing that law right now,” said Gregory Dober, a healthcare ethics advocate and advisor at Pitt’s Center for Bioethics & Health Law. In his experience, wardens often employ lockdowns and solitary confinement when they run into staffing trouble, because such actions lighten the workload of corrections officers. “How does he get away with it? Well, it’s called the Jail Oversight Board. If the oversight board is not criticizing him or saying enough is enough, who else does anything?”

Representatives from the jail declined to be interviewed and did not respond to the details presented in this story with a list of questions.

Over the years, the jail’s use of solitary has been targeted in lawsuits against the county and warden Orlando Harper.

Jules Williams, a Black transgender woman, was arrested on Sept. 30, 2015 and taken to the Allegheny County Jail. She has been receiving hormone treatments since she was 18 years old, and, at the time, had undergone gender-affirming medical care. But the jail housed Williams with men because she had “both male and female parts,” according to a lawsuit Williams filed in 2017 with the ACLU-PA in the Allegheny Court of Common Pleas.

She requested segregated housing for her protection. The jail granted her request, but placed her in a solitary confinement cell with Djamal Eleam, a convicted sex offender who had made headlines weeks earlier because the jail mistakenly released him. Eleam allegedly raped Williams repeatedly over the next four days before jail staff removed him from the cell. Even after Eleam was separated from Williams, she told her public defender that jail staff forced her to shower with men, some of whom would come to her cell at night and masturbate on her.

In December 2016, five women filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the jail, Harper, and others because they were held in solitary confinement while they were pregnant. In November of that year, Jill Hendricks, who was eight months pregnant, was placed in solitary confinement for nine days, during which she was only let out of her cell once, for one hour, on Thanksgiving Day.

In May 2016, Mersiha Tuzlic, who was two months pregnant, was placed in solitary confinement for 22 days. She filed a grievance with Harper on her 11th day of confinement, stating that she had a pregnancy classified as high-risk, and wanted at least one hour of recreation outside of her cell. She received a response weeks later. Her grievance was dismissed by someone who wrote over her statement, “If this is a problem don’t come to jail.” In October, she was sent to solitary again for another 11 days.

In September 2020, five people with severe mental illness filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the jail, Harper, and others alleging they were placed in solitary confinement for long periods of time, tased, and strapped into restraint chairs.

The pregnant women reached a settlement with the county, Harper, and other defendants in late 2017 for $90,000 and changes to the jail’s policy. Williams settled her case for $300,000 in 2022.

The case with the plaintiffs who suffer from mental illness is still ongoing. Two of their experts reviewed defendant depositions, jail policies, case files for a representative sample of incarcerated people with mental illness, among other jail documents. The experts cited aggressive use of force by jail staff, a lack of appropriate health care and health staffing, and the repeated use of segregated housing despite the 2021 referendum.

“The measures taken by Allegheny County to avoid solitary do no such thing,” wrote Bradford Hansen, a former warden with more than 42 years of corrections experience. “This violates all applicable correctional standards and is objectively unreasonable.”

According to data maintained by the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (DOC), the Allegheny County Jail had the highest number of documented use of force incidents — 455 — out of all Pennsylvania county jails in 2021. Since 2020, medical staff vacancies have soared to 88 unfilled positions out of a budgeted 162. And even though some positions have been temporarily filled through staffing agencies, 23% still need to be filled. The jail’s chief medical director was also recently reassigned without a permanent replacement in place.

In fall 2020, Janet Bunts, a health services administrator for the jail, quit her job after just three months. In December 2020, she told the Tribune-Review that her bosses were not providing proper medical care to incarcerated people. “Correctional medicine is not for everybody,” Bunts said. “It’s going to take effective leadership to change that place.” Last spring, the jail’s corrections officers’ union contemplated a no-confidence vote in Harper, and in the summer, the union’s president filed a complaint that he was being targeted for speaking out about the jail’s problems.

A 2021 ACJ survey of 1,418 incarcerated people by the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work found that two thirds were dissatisfied with the medical care they received, with some saying they did not receive proper care or treatment. In 2022, the Pennsylvania Prison Society used prison-issued tablets to collect 330 responses to a health care survey. More than half of the respondents who requested medical services said they had not received health care.

“Neither a staff crisis nor the health crisis is an excuse that people’s basic constitutional rights should not be respected and maintained,” Noah Barth, the Pennsylvania Prison Society’s prison monitoring director, said. “When you have a situation where over half of the respondents are saying they’ve requested medical care and have not received it, that points to dysfunction, breakdown, and basic provision of care. And that should be a deep concern to the warden and anybody else looking at the jail.”

Unannounced visits conducted by two members of the Jail Oversight Board on Oct. 27 and Nov. 14, 2022 also found medical staff complaints and long waits for medical care.

“Unfortunately, many people in the ACJ come from vulnerable populations, and many bring with them serious medical conditions that have not been properly treated for extended periods,”Harper wrote in a response to the 2022 Prison Society survey.

In an op-ed published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in July 2022, Harper lamented that the public wasn’t hearing the jail’s success stories. “The only news that gets coverage at the jail is bad news,” he wrote. The same day Harper’s op-ed was published, an incarcerated person died in his jail. It was the fourth in-custody death that year.

While the average number of incarcerated people at the Allegheny County jail dropped by almost 1,000 at the outset of the pandemic, deaths have grown substantially. From 2020 to 2022, at least 17 incarcerated people died at the jail, compared to just 10 in the three years prior. According to a report by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care released last month that examined each of the incidents, the death rate for the jail since 2020 is nearly three times the average mortality for local jails across the United States. The six deaths at the jail in 2022 put its death rate above the much larger and infamous Rikers Island Jail Complex in New York City for last year.

Staff surveyed in the report said medical training, and, especially, CPR training were major concerns, along with communication of critical medical incidents “specifically deaths and suicides, or follow up or corrective information.”

The report also noted that “three of the findings had causes of death that were not explained by the documentation provided.” This included a man who died of a ruptured spleen, a man who died of blunt force trauma to the head, and another who died from asphyxiation where “the autopsy found the manner of this death undetermined.” In that case, the jail attributed the man’s death to him choking on food, although the corrections sergeant turned off his body camera before entering his cell, so the report’s team could not confirm the circumstances of the incident.

On March 2, people gathered at the Allegheny County Courthouse for a monthly Jail Oversight Board meeting. Harper sat with his back to the public as each person spoke about conditions of confinement at his jail. Many mentioned the low quality health care. One speaker played audio of a man who said he was put in solitary weeks ago. “The hole? That’s the dog kennel,” said the man in the recording. “They’ll send you in there for anything.”

Juana Saunders, Gerald Thomas’s mother, spoke towards the end of public comment. “We don’t know if my son’s life would have been spared or not. But what we do know is that he died in the Allegheny County Jail,” Saunders, who was dressed in all white, said from the podium. As she spoke her voice rose in anger and she jabbed her finger at the board to take action.

Last month, Saunders said that she’ll sometimes cry for hours when she thinks of her son, and still has trouble visiting his grave. She spent over $8,000 burying her son near her father and niece, who both died during the past four years. On Feb. 25, Saunders, through an advocate with the Abolitionist Law Center, started a GoFundMe in the hopes of raising money to put a headstone on his plot.

“Y’all need to get on your job and make this man do what he need to do,” she said during the Jail Oversight Board meeting, pointing at Harper, “because they are killing people inside that jail, and they’re pushing the bodies out the door. And it’s not fair to me, it’s not fair to my family, it’s not fair to all the other families of people who died in that jail.”