In historic North Carolina hearing, Joe Freeman Britt’s troubled past as prosecutor looms

The proceedings are before a Johnston County Superior judge, but former Roberson and Scotland County prosecutor Britt’s legacy hangs over them.

This story was produced in partnership with The Border Belt Independent.

In February and early March, a Johnston County Superior Court judge held an evidentiary hearing related to a claim filed by Hasson Bacote that race played an impermissible role in the jury selection of his first-degree murder conviction and death sentence.

For nearly 14 years, Bacote, a Black man, has sought relief under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act, a 2009 law that gave people on death row the chance to challenge their death sentences. The act said if death row prisoners could prove racial bias was a significant factor during their trial they could have their sentence reduced to life in prison without parole. But in 2013, after just four claims were heard, state lawmakers repealed the RJA, leaving Bacote and more than 100 other people on death row in limbo.

It wasn’t until 2020 that the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that claims filed prior to the RJA’s repeal could proceed. As a result of the ruling, claims of racial bias by Bacote and the majority of the state’s death row can be heard. Bacote’s evidentiary hearing in front of Judge Wayland J. Sermons Jr. was a step forward toward relief from a death penalty system that advocates and attorneys say is rife with racism.

During the two-week hearing, the first under the RJA since the state Supreme Court’s ruling, Bacote’s attorneys drew on statistical analysis of jury selection data showing Black people are much more likely to be struck from serving on capital juries.

Currently, people of color make up more than 60 percent of the state’s 136 death row prisoners, though North Carolina is nearly 70 percent white. Bacote’s attorneys cited state and county history — such as cross burnings and the 1986 police killing of Ellis King Jr., an unarmed Black man — to argue that the state’s application of the death penalty is fraught with racial bias.

“The racism in North Carolina’s application of the death penalty is so clear it’s blinding,” Henderson Hill, Bacote’s lead counsel and senior counsel with the ACLU, said.

A decision in the case is expected later this spring.

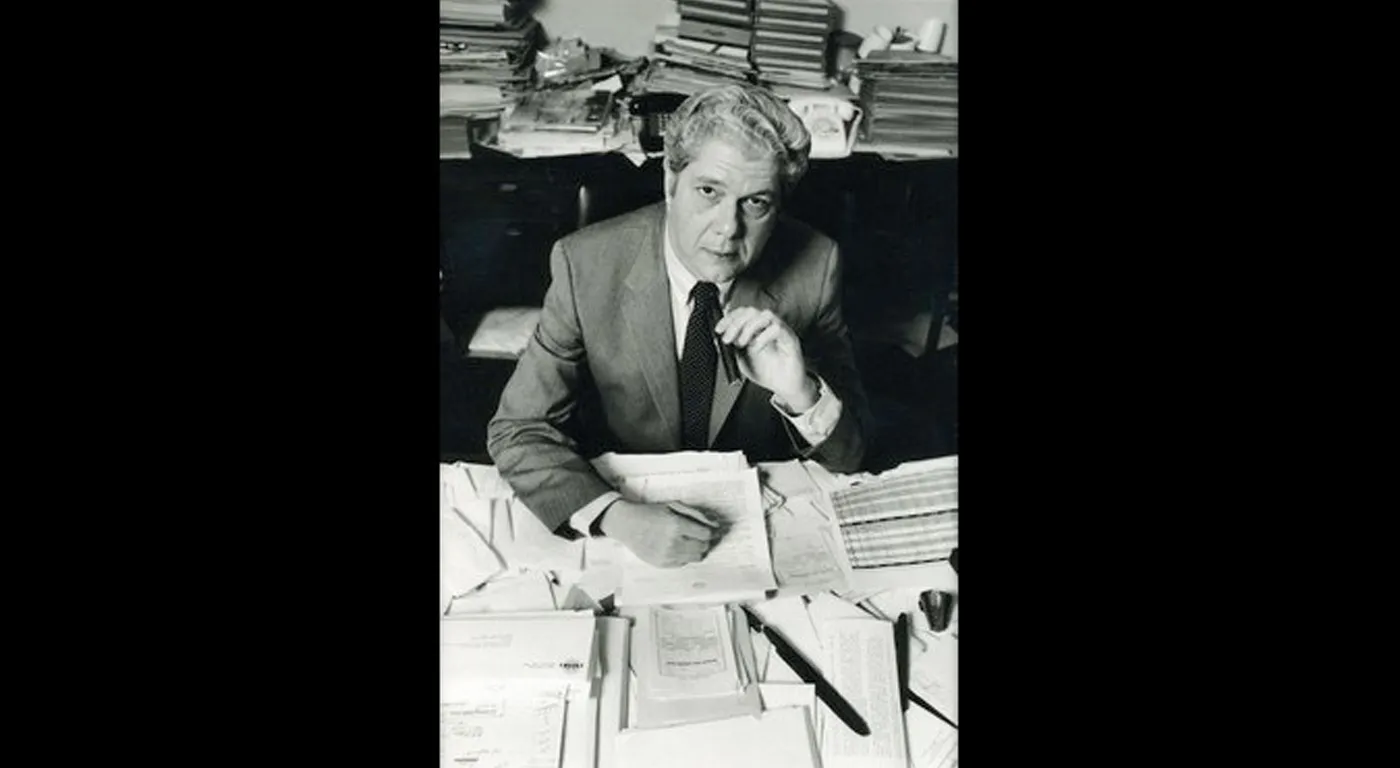

Though he was the district attorney for Robeson and Scotland counties, Joe Freeman Britt loomed large over Bacote’s hearing. Advocates and defense attorneys believe that Britt was a uniquely damaging influence in the state’s troubled death penalty system.

America’s Deadliest Prosecutor

In 1978, the “Guinness Book of World Records” named Britt the “deadliest prosecutor” for obtaining 23 death sentences in a 28-month period. During Britt’s tenure as DA, which lasted from 1974 to 1988, he secured 38 death sentences, though many were later overturned. Britt was found to have committed misconduct in 14 capital cases, according to a 2016 report from Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project. The state executed two people Britt sent to death row; he died in 2016.

Britt is perhaps most notorious for sending brothers Henry McCollum and Leon Brown, two intellectually disabled Black teens, to death row in 1984 for the murder of an 11-year-old girl, even though the case against them was weak. One witness told police Henry was involved in the murder simply because he looked weird. In 1994, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia cited Brown and McCollum’s case as a reason why the death penalty was necessary and execution by lethal injection wasn’t cruel and unusual. But the pair were exonerated in 2014 after serving more than 30 years in prison; The New York Times described the case as a “judicial horror story.” DNA evidence pointed to another man, who Britt had sent to death row for committing a similar crime. In 2021, a jury awarded McCollum and Brown $75 million in a federal civil rights case they brought over their wrongful convictions.

“It’s such an outrageous thing that happened to these men and for this guy to go and lament that they hadn’t been executed after it came out he had convicted the wrong people — I’m hard pressed to think of someone who just did more to illustrate their unfitness for a position of prosecutor,” said Ian Mance, senior counsel at Emancipate NC, a legal nonprofit organization in Durham.

In an interview with the Border Belt Independent, Ken Rose, an attorney who represented McCollum prior to his exoneration and the former executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, referred to Britt as an “early leader and the early violator” in the state’s death penalty system.

“You have prosecutorial misconduct. You have juror misconduct. You have racial discrimination — all of that took place on his watch,” Rose said.

But Britt’s work wasn’t limited to Robeson and Scotland counties. For years, he trained prosecutors at the National College of District Attorneys in Houston. According to a transcript of a 1985 “60 Minutes” segment, Britt told prosecutors at one training session it was their responsibility to “tear that jugular out” of witnesses. He also compared the courtroom to a crucible where prosecutors had to heat up in order to discover the truth.

“Within the breasts of every one of us burns a flame that constantly whispers in our ear, ‘Preserve human life, preserve human life, preserve human life at any cost,” Britt said. “And as brutal as it may sound, it is the prosecutor’s job to extinguish that flame in the breast of every one of those jurors for the purposes of that case and for the purpose of that defendant.”

Britt served on the executive committee of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys, an organization created by lawmakers in 1983 to represent the interests of the state’s prosecutors. The group organizes training programs for prosecutors, including one in 1995 that produced a training document that offered explanations prosecutors could use if defense lawyers challenged a peremptory strike under Batson v. Kentucky, a 1986 United States Supreme Court decision barring prosecutors from preemptively striking prospective jurors solely based on their race.

“If this is how he was operating, what was it that he was doing that made him an appealing candidate to serve on this executive committee?” Mance of Emancipate NC said. “I don’t think anything he was doing was a secret.”

Lingering Legacy

Britt was lionized among prosecutors, according to Gretchen Engel, executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. She told the BBI that it will take a long time to remedy the prosecutorial culture he created.

That culture was at the center of Bacote’s hearing.

Bacote’s attorneys drew from more than 680,000 pieces of discovery turned over by the state culled from prosecutors’ files in about 500 capital cases dating back to 1980. The documents included court transcripts and handwritten notes related to jury selection in 70 counties.

In one capital case in Scotland County, in 2003, prosecutors circled parts of prospective Black jurors’ questionnaire responses including NAACP membership and viewership of BET or movies like “The Color Purple.”

During jury selection in 1992 for Herbert Barton’s first-degree murder trial, a Robeson County prosecutor noted that a white juror lived in a “Black section,” according to documents. The North Carolina Supreme Court vacated Barton’s death sentence in 1994. He was re-sentenced to life in 2001. Today, six people on North Carolina’s death row were convicted in Bladen, Columbus, Scotland and Robeson counties.

In a 1996 Johnston county case, prosecutors created a category in their notes called “Jury Selection Excuses,” with names of each juror and reasons to exclude them. For one Black juror, the reason to excuse him was listed as “Race = Black.”

Prosecutors in Cumberland County described a Black male juror to be “strong as a bull” in one case, while the word “thugs” and “blk wino” were written next to the names of other prospective black jurors in another.

In a late 1990s first-degree murder case involving Jimmy and Richard Smith, a Martin County prosecutor wrote on a jury summons list that a white juror was “good” and that she would “bring her own rope.”

Seth Kotch, an associate professor of American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, testified during Bacote’s hearing that this note indicated that the prospective juror may be seen as sympathetic to the prosecution and that the juror could bring the same “spirit of vengeance” connected to the state’s long history of lynching to the trial or jury selection process.

“When the prosecutor is saying, ‘She’s a good one, she’ll bring her own rope,’ they’re saying a juror that brings those racial biases and prejudices to the box — that’s a keeper. That’s one of ours,” the ACLU’s Hill told the BBI.

Bacote’s legal team also cited language by Gregory Butler, the lead prosecutor in Bacote’s case, during closing arguments in two capital trials. In 2001, Butler compared three Black defendants to “predators of the African plain” and described Bacote as a “thug” during his 2009 trial.

During the hearing, Butler testified that his comments weren’t motivated by racial bias. He said that when he compared Black defendants to “predators of the African plain,” he was trying to explain what it means to “act in concert,” a complex legal theory where a defendant can be guilty of a crime even if they didn’t take part in all of its elements. Butler said he used the word “thug” only to describe the kind of person capable of committing robbery.

After Bacote’s attorneys presented evidence showing that Butler struck prospective Black jurors in four capital cases at a rate 10 times higher than white people, Butler testified that he never struck a juror for an improper reason.

“I’ve never, ever struck a juror without having race-neutral reasons,” he said. “And I’d go farther to say that I don’t believe I’ve ever struck anybody for a racial reason.”

In Johnston County, researchers found that Black people were four times more likely to be struck from jury pools in capital cases between 1985 and 2011. Statewide, during that same time period, Black people were struck at a rate that was 2.5 times higher. Bryan Stevenson, the acclaimed civil rights attorney and author of “Just Mercy,” testified that there’s clear evidence of racial bias in jury selection in North Carolina.

Another witness testified that every Black person tried capitally in Johnston County between 1991 and 2014 was sentenced to death.

Bacote’s legal team also pointed to Johnston County’s racist history, which includes numerous lynchings. An expert witness testified that billboards promoting the Ku Klux Klan were erected along county highways as late as the 1960s and 1970s. One sign read “This is Klan Country” and featured a hooded figure on horseback holding a burning cross.

The state argued that Bacote’s death sentence didn’t spring from racial bias, but from the seriousness of his crime; he was charged with killing 18-year-old Anthony Surles during a robbery. Closing arguments are expected later this spring. Attorneys and advocates said that Judge Sermons’ decision could guide how judges across the state will handle RJA claims that come before their court.

Though the racist billboards, Klan marches and cross burnings are in Johnston County’s past, Hill said “the notion that the courthouse in Johnston County is a white institution, staffed by white people, and justice administered by white people — that lingers.”

Hill said the legacy of Britt, who he described as the type of prosecutor who traded “in on all of the worst tropes and stereotypes and dehumanizing language” lingers too.

For Engel, from the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, and others advocating against the death penalty in North Carolina, Britt’s influence is clear.

“There is a pretty direct line from somebody like Joe Freeman Britt to a prosecutor who would compare three young African-American defendants to animals, and not just any animals but animals in Africa,” she said.