White Riot

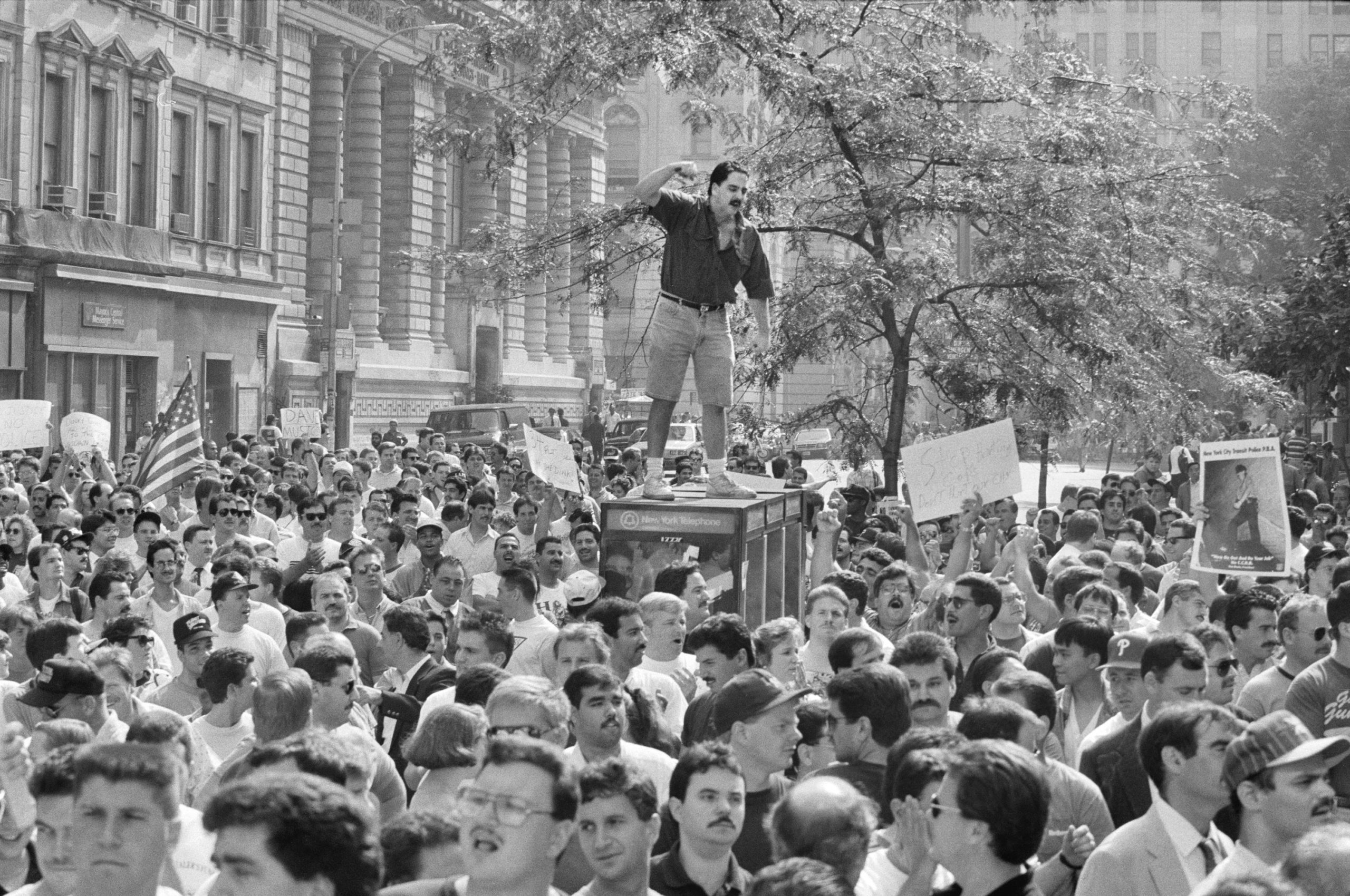

In 1992, thousands of furious, drunken cops descended on City Hall — and changed New York history.

This story was produced in partnership with New York Magazine.

At around 11 a.m. on September 16, 1992, Norm Steisel heard a roar from outside his office in City Hall. Peering out the window, he saw thousands of off-duty police officers filling the narrow park that surrounds the building, a grand neoclassical structure that, all of a sudden, had started to feel like the tightest of traps.

Steisel, then first deputy mayor of operations, heard officers chanting, “Dinkins gotta go!” and “The mayor’s on crack.” They carried signs bearing racist cartoon images of Mayor David Dinkins with humongous lips and nose and an Afro, including several calling the city’s first Black mayor a “washroom attendant.”

The officers had a permit to protest, which confined the demonstration to Murray Street, a road perpendicular to City Hall lined with Irish pubs. They were mad that Dinkins was pushing a bill that would change the composition of the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), the oversight body that examined complaints of police misconduct, from half-cop–half-civilian to all civilian and making it independent of the New York Police Department. The bill was part of a wave of measures proposed by cities across the country in the wake of the shocking, caught-on-tape beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles in March 1991 and, just months earlier, the April 1992 acquittal of all four officers in the case.

Dinkins was uptown attending a funeral, which meant that Steisel was the highest-ranking person in the administration inside City Hall. Days later, Steisel talked to Phil Caruso, president of the New York City Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (which later changed its name to the Police Benevolent Association, or PBA). Caruso, a powerful figure who was respected by the rank and file, tried to explain the officers’ anger.

“‘You don’t treat these guys with respect,’” Steisel recalled Caruso telling him. “‘When you create a Civilian Complaint Review Board, which is going to challenge everything they do, it’s just going to respond to “Black whining.”’”

Steisel remembered Caruso telling him, “‘If you don’t respect them, you’ll never have a safe city again.’”

The day of the protest, Rudy Giuliani was also outside the building with a microphone. Giuliani, a former U.S. Attorney and failed mayoral candidate in 1989, declared, “The reason the morale of the police department of the City of New York is so low is one reason and one reason alone: David Dinkins!” The crowd roared.

“The mayor doesn’t know why the morale of the police department is so low,” Giuliani said. “He blames it on me. He blames it on you. Bullshit!” Giuliani then attacked an anti-corruption commission impaneled by Dinkins, which he said was created “to protect David Dinkins’s political ass.” More cheers rose from the crowd.

The demonstration began to spiral out of control, amplified by officers drinking at the pubs on Murray Street. Thousands more had shown up than were expected. Deputy Mayor Fritz Alexander called the police on the police. Acting Police Commissioner Ray Kelly dispatched a phalanx of officers to City Hall for crowd control.

That was when Steisel started to get scared.

“I was getting concerned they’re gonna storm the building,” Steisel said. “I mean, these fucking guys are crazy.”

This was the beginning of an outburst of violence that, for various reasons, has been all but scrubbed from New York’s historical memory. It not only involved Mayor Dinkins but was a formative experience for two future mayors and the city’s likely next mayor — who back then was a 32-year-old transit-police officer. “It’s almost equivalent to what we saw at the Capitol,” Eric Adams told me recently, referring to the Trump-inspired insurrection on January 6.

A closer look back at the City Hall Riot, as it deserves to be known, also serves as a reminder of the challenges Adams himself will face when he takes office next year: a police department that, all these decades later, often seems still hell-bent on resisting meaningful reform.

At the time of the riot, Bill de Blasio was a 31-year-old junior aide in the Dinkins administration. Thirty years later, current and former aides say, the mayor still tells staff that the riot made a huge impression on him as a young person working in politics — a factor that no doubt shaped de Blasio’s early pledges to reform the police and showed him what can happen when the police turn on the mayor.

Una Clarke, then a member of City Council, tried to enter the building, but an off-duty officer blocked her from crossing the street. She later said the white officer turned to another officer next to him and said, “There’s a n – – – – – who says she’s a councilmember.”

A group of officers lined up in front of the doors to City Hall. At one point, they let a woman attending the protest, who may have been the widow of a fallen officer, inside. “Someone yelled that they had arrested her and the mob of officers outside rushed the building,” remembered Bob Liff, a former City Hall reporter at Newsday who was inside the building at the time.

“In all my years there, with lots and lots of demonstrations, it is the only time I ever remember the cops slamming the doors shut and putting the bars across the doors to keep anyone from getting in,” Liff said. “It is also the only time I remember feeling any sense of fear inside City Hall.”

Officers climbed atop vehicles parked in front of the building, kicking and pummeling them. Then the sea of officers, repelled from the doors of City Hall, turned and headed for the Brooklyn Bridge, just a few hundred feet away from the building’s gates. They stormed over it. (At least one on-duty officer opened up the barricades for the protesters.)

New York Times reporter Alan Finder followed the rioters onto the bridge and was kicked in the stomach. John Haygood, a Black cameraman for CBS, was called the “N-word” by people in the crowd.

City Councilmember Mary Pinkett, in a car on the Brooklyn Bridge, got caught in the traffic. She later recalled off-duty officers shook and rocked her car in order to frighten her and the elderly Black passengers inside. About a dozen mounted officers sat on their horses and didn’t act to quell the riot, one contemporaneous Newsday report said.

When Eric Adams arrived downtown, there was a full-blown riot going on. “When people are riled up to that level, you leave the state of being rational to the irrational behavior of a moblike atmosphere,” he told me.

Some of the city’s newspaper columnists, including Jimmy Breslin, the poet laureate of the city’s blue-collar working class, were repulsed. According to a column he wrote the next day, Breslin saw an officer in a PBA shirt saying to a female television reporter, “Here, let me grab your ass.” He saw one officer yelling “across the beer can held to his mouth, ‘How did you like the n – – – – -s beating you up in Crown Heights?’” Another said, “Now you got a n – – – – – right inside City Hall. How do you like that? A n – – – – – mayor.”

“They had beer and they wore guns and they all thought it was great to be young and drunk and ignorant,” Breslin wrote. “They were screaming that the mayor, this Black mayor, wants a Civilian Review Board. And they put it right out in the sun yesterday in front of City Hall: We have a police force that is openly racist and there is a question as to what good they possibly can be in a city that will be famous forever as existing grandly with every other color there is between here and Mars.”

“We have been saying for years that the police department is comprised of racist Long Islanders who come into the city by day and leave at night with their arrogant attitudes and believing they are above the law,” Adams told newspaper reporters right after the riot. “Well, finally, the entire city was able to see what we’ve been talking about.” Adams also told Newsday that the riot was “right out of the 1950s: a drunk, racist lynch mob storming City Hall and coming in here to get themselves a n – – – – -.”

He was “just angry” at the time, Adams told me, nearly 30 years later. “I was just angry because I knew. Imagine the symbol of this. Here you had the first Black mayor, the chief executive of the city. And they [the rioters] basically said, ‘We don’t care who you are, if you’re Black.’”

Adams remembers he chose those words carefully.

“History has so many examples of storming places, houses, houses of worship places and going in and grabbing a Black person, a man in particular, and hanging, beating,” Adams said. The City Hall riot “should be part of the historical narrative of these types of drunken lynch mobs,” he said.

He said police participation in the riot wasn’t counterintuitive because in the American history of lynch mobs, “many of them were being led in the South by sheriff’s marshals and other lawmakers.”

Dinkins’s effort to reform the Civilian Complaint Review Board was not the only nominal catalyst for the riot. Fear of crime gripped the city that summer, hardening and embittering the New Yorkers who’d congratulated themselves on electing their first Black mayor just three years earlier. Dinkins had brought crime rates down — from a record of 2,262 homicides in 1990 to 2,020 in 1992 — but they were still elevated (last year, for comparison, there were 468 murders in New York). Racial tensions also simmered: In August 1991, a riot broke out between the Black and Jewish residents of Crown Heights. A young boy and a young Jewish man were killed, stores were destroyed, and many were injured. It took police days to restore order.

In early July 1992, in Washington Heights in upper Manhattan, white officer Michael O’Keefe shot and killed young bodega clerk Jose “Kiko” Garcia, an undocumented immigrant from the Dominican Republic. Neighbors said that, prior to the shooting, they witnessed O’Keefe beat Garcia with his police radio.

Anti-police rage boiled over into three nights of protests that turned into riots uptown. Cars were burned, stores looted. People in the neighborhood were particularly angry that O’Keefe was a member of a plainclothes unit from the long-troubled 34th Precinct, which was rumored to be full of dirty cops who shook down drug dealers for money and was under investigation by the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York.

In an attempt to defuse tensions, Mayor Dinkins invited Garcia’s family to Gracie Mansion. Cops — who’d been working without a contract for two years — were already frustrated with Dinkins, despite the fact he’d passed legislation adding thousands of new officers to the force and had shielded the department from budget cuts. The police called Garcia, who had a single drug conviction, a “drug dealer” in the pages of the city’s tabloids, outraged at the sympathy Dinkins showed to the Garcia family.

Even though O’Keefe was celebrated by the police at City Hall that day, he is surprisingly critical of the riot, though he insists it should be called a demonstration. “When the thing broke up, it went bad,” O’Keefe told me. “They basically took the bridge, which was hysterical because we were so critical of Al Sharpton and all these people who took the bridge whenever they had a stubbed toe.”

On September 3, a grand jury impaneled by then-Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau cleared O’Keefe of Garcia’s killing. A week later, Morgenthau issued a 45-page report about the incident, citing inconsistencies between witness testimony and physical evidence. “The version of events which they have offered to investigators is not only not corroborated by the physical evidence in the case, it is actually contradicted by that evidence,” Morgenthau wrote. The newly exonerated O’Keefe showed up the day of the protest at City Hall and was hailed by the crowd as a hero.

In the immediate aftermath of the riot, there was outrage from both politicians and observers in the media. Breslin and other pundits speculated that the cops had dealt Dinkins a winning hand that would ensure his reelection the next year and that Giuliani had badly damaged his political career by inciting a riot. “They used racist language, carried racist signs, and called the Mayor a n – – – – -,” Times columnist Anna Quindlen wrote. “Nearly a third of New York City’s police officers live on Long Island, and some of them like to congratulate themselves on getting out of the hellhole they are sworn to protect.”

A few days later, Dinkins, a solemn, quiet, and composed person who took pains not to lose his cool in public, let his composure slip.

“If some officers in full view of a camera and public and their superiors or officers would use racial slurs, yelling ‘n – – – – -s,’ and some of the signs they were carrying … I fear how they would behave when they are out in the streets,” Dinkins said, visibly angry.

A group of Black officers that included Adams demanded an inquiry. Speaker Peter Vallone — who had been disinclined to support Dinkins’s CCRB legislation before the riot — was incensed by the behavior on display during the riot. Multiple councilmembers’ cars were badly damaged. Newsday reported Brooklyn seeing “City Councilman Herb Berman watch helplessly as the rioters tore a headlight from his Audi parked outside.” (Vallone ended up pushing through a compromise bill to change the composition of the CCRB.)

But as the days passed, the atmosphere changed. Caruso, the PBA president, was defiant. Giuliani, far from fearing the riot’s impact on his political future, was ecstatically happy about his participation in it.

“One of the reasons those police officers might have lost control is that we have a mayor who invites riots,” Giuliani told reporters a few days later. He said he felt empathy for the police officers, not the people frightened by them. “I had four uncles who were cops,” he said. “So maybe I was more emotional than I usually am.”

Giuliani said the real issue was not racism among the rioting officers, but whether “the relatively minor occurrence of racial epithets, if they occurred at all, has been made the focus of this rally for political purposes.”

Caruso said the officers’ behavior was understandable given the summer’s political battles over policing. “Without apologizing for the protest, Mr. Caruso said the raucous behavior of about 4,000 officers among the 10,000 protesters the previous day was ‘a human reaction,’ and that police ‘feel like pawns in a very complex game of political chess,’” the New York Times reported.

“Sometimes, in order to convey a message clearly and graphically, especially on the part of police officers, you have to see it, feel the intensity,” Caruso argued. He said the officers were “humans, not robots.”

Caruso even blamed City Councilman Guillermo Linares, a Dominican American who represented the Washington Heights neighborhood and was sharply critical of the police in the wake of the Garcia killing. “You are responsible for what happened yesterday and so is the mayor,” Caruso told Linares during a council hearing a day after the riot.

Somehow, the major papers in New York began to accept some of Giuliani and Caruso’s criticisms. It probably didn’t help that footage from the City Hall riot was limited. Footage from at least one television news report still exists, which aired on NY1, a local news station then in its infancy. Most of the coverage was filtered through the print and radio reporters who covered City Hall. (A short piece by Washington Post columnist Radley Balko about the riot, written in the wake of Trump’s election in 2016, remains one of the few major media accounts of the event beyond the contemporaneous reporting.)

Some media assigned blame for the riot, the police reaction, the era of bad feelings not just to the police but in the weeks after the riot, increasingly, also to Dinkins. By calling out racist behavior, Dinkins was “playing the race card.” A New York Times editorial from late September apportioned some blame for racial tension to Dinkins, for showing sympathy to Kiko Garcia’s family. In doing so, Dinkins “trampled on the understandable sensitivities of the police—and indeed, he has not yet shown them adequate concern,” the editorial said.

Another Times editorial from the first week of October applauded Dinkins, who’d by then stopped criticizing police for racist language, as polls showed voters blaming both the mayor and Giuliani for playing “the race card.”

“Mayor David Dinkins’s more conciliatory approach to the Police Department is most welcome,” the editorial said. “New York City needs a break from the tensions generated by the bitter police demonstration three weeks ago, and that means lowering the voices on all sides.”

It was Dinkins who needed to apologize if he wanted to stay mayor, wrote Newsday columnist Dennis Duggan. “He might start with an apology to the cops who he dissed, as they say on the streets, by taking the mother of the dead drug dealer into Gracie Mansion and then by paying for the dead drug dealer’s funeral with city tax money,” he wrote.

In a September 18 op-ed, A.M. Rosenthal, a former executive editor of the Times who had become a columnist, described the slain Garcia as “part of the contemptuously open drug operation that dominates life in Washington Heights, day and night. He used drugs heavily, was a convicted drug peddler, a probation violater, a fugitive.”

“The mayor properly protested use of the word ‘n – – – – -,’” New York Post columnist Ray Kerrison wrote, “but he is silent when his friend Charles Rangel calls Ross Perot a ‘white cracker.’”

Dinkins “combed the press for the most racially inflammatory item he could find and made sure it got maximum attention,” another Post columnist, Scott McConnell, wrote, chiding Dinkins for drawing attention to the racial slurs officers used at the protest. “It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the mayor is doing all he can to defeat and humiliate the NYPD — and with it the millions of New Yorkers who need and support the cops. His success — thank goodness — isn’t assured. For how could such a victory be anything but an utter catastrophe for the city?”

Although Dinkins “framed the protest almost exclusively in racial terms” and despite the fact “some racial slurs were used by protesters at the demonstration and a small number held racially provocative signs,” New York Times journalist Catherine Manegold reported on September 27, “race did not appear to form a central theme of their [police’s] complaints, which focused on mayoral policies they felt undercut the police.”

But to many Black New Yorkers, race was exactly what the rally was about. “This rally wasn’t about the CCRB or Washington Heights,” a high-ranking Black officer told Newsday shortly after the riot. “It’s about race. It’s about white cops who don’t live in our city. It’s about white cops who don’t want any part of a Black mayor and will never accept a Black mayor. That’s what this is really about.”

Adams had known for years how some of his fellow officers felt about Dinkins. In January 1990, right after Dinkins was inaugurated, Adams put a photo of Dinkins on the front page of the Daily News on his desk at the Transit Police Bureau’s Data Processing Unit. “Because it was a proud moment,” he told me. “And the next day I came in, someone vandalized it, and wrote ‘washroom attendant’” on the photograph.

The riot spawned two inquiries, nominally aimed at holding officers who participated accountable: One was led by Manhattan DA Morgenthau and another by Ray Kelly. Some Black police officers, including Adams, wanted a special prosecutor to be appointed, arguing that the DA’s investigation would be tainted by police influence. Dinkins, ever conciliatory, said he didn’t see a need for a special prosecutor.

Less than 14 days after the riot, acting Police Commissioner Kelly issued a 13-page interim report on the City Hall riot that didn’t mention Giuliani’s participation at all. Somehow, police only identified 87 of the estimated 10,000 officers and their supporters who participated. Just 42 faced disciplinary charges. And only two officers were suspended: 38-year-old Michael Abitabile, who was on duty and charged with opening the barricades to protesters and uttering racial slurs, and off-duty Officer Thomas P. Loeffel, 27, who had blocked traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge. Another 26 off-duty cops identified as blocking bridge traffic faced disciplinary proceedings.

Among the 42 officers facing discipline were 13 on-duty officers assigned to control the crowd and a helicopter pilot who blared his chopper’s horn in support of the protesters. And while Kelly condemned the use of racial slurs by officers, by the time the report came out, his stance had softened considerably. Kelly announced a new departmental policy that officers who use racial slurs “absent extreme emotional distress” would be fired.

The media played along. The New York Times editorial board praised the report.

“The report is no whitewash,” the board said. “Mr. Kelly deserves credit for the promptness of his account, and its reassuring tone of censure.”

And even the mild report drew criticism from supporters of the police. Giuliani, ever ready to press his advantage, called it an attempt to make the police “scapegoats for political gain.”

The City Hall riot began to fade into history. By the next year, as Giuliani prepared to challenge Dinkins for the office of mayor, an internal‐strategy report prepared for his campaign devoted more than 50 pages to the City Hall riot under the heading “RACIST.” “When dealing with direct questions about the police rally, Giuliani should acknowledge and criticize the underlying racial nature of the protest,” the report read.

But the only riots anyone seemed able to remember were the ones that Dinkins had allegedly mishandled — the ones where Black people were doing the rioting. On the campaign trail, Giuliani hammered Dinkins over the Crown Heights riot.

Giuliani was also adept at playing the victim. He threw a fit when a Black minister who supported Dinkins compared some of his supporters to “fascist elements.” Giuliani said that calling his supporters fascists was tantamount to an ethnic slur, because of his Italian heritage.

Then-Governor Mario Cuomo gave the Giuliani campaign what amounted to an assist, allowing a referendum on whether Staten Island — the city’s whitest, most Republican borough — could secede from the city to be placed on the November ballot, juicing turnout among people inclined to support Giuliani.

On Election Day in 1993, Giuliani’s campaign hired off-duty cops, firemen, and correction officers to monitor Black election districts for voter fraud. Ray Kelly assigned 52 captains and 3,500 officers to the city’s polling places over the objections of the Dinkins campaign, which believed that the effort would intimidate Democratic voters. Giuliani won by a slender margin. The Times noted that he swept “the white ethnic neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island that have been his political base.”

At his Election Night victory party, Rudy thanked the NYPD and FDNY for helping him win.

Nearly 30 years later, only some of what ailed the NYPD 30 years ago has been mended. The department’s rank and file has become more racially diverse, but its top ranks are still overwhelmingly white. Earlier this year, New York Attorney General Letitia James sued the NYPD over what she claimed was a pattern of excessive force and false arrests during the 2020 George Floyd protests. “There is no question that the NYPD engaged in a pattern of excessive, brutal, and unlawful force against peaceful protesters,” James said.

The CCRB is still seen as an ineffective bulwark against police misconduct, and the NYPD as its own fiefdom impervious to mayoral control. The city’s police unions are as pugilistic and right-leaning as ever; last fall, the PBA endorsed Donald Trump for reelection. (Caruso of the PBA died on August 8 of this year.) And last week, de Blasio announced that he was launching an investigation into right-wing extremism in the NYPD, after WNYC-Gothamist reported that several officers had ties to the anti-government militia the Oath Keepers.

“Whether we like it or not, race is the silent visitor,” Dinkins said in a campaign speech at a fundraiser in October 1993. In his 2013 memoir, the former mayor was more direct about both race — he said he lost his reelection bid because of “racism, pure and simple” — and the City Hall Riot.

He accused Giuliani of “all but inciting the police to riot” and asked, “Would the cops have acted in this manner toward a white mayor? No way in hell. If they’d done it to Ed Koch, he would have had them all locked up.”

It’s taken decades, but in large part due to the George Floyd uprising and other protests against police brutality, Dinkins’s sentiments about race — and Rudy — have become closer to common wisdom.

The city is on the precipice of electing only its second Black mayor in its more than 400-year history. But Adams relishes sparring with the left, particularly on policing, which his critics say is evidence that little will change under his administration. Still, Adams can surprise — in mid-September, he returned a $400 donation from Sergeants Benevolent Association president Ed Mullins after he called Representative Ritchie Torres a “whore.”

When pressed, Adams maintains that a key element of police reform is identifying rotten apples and holding them accountable. “I saw some of the most racist, hateful, mean-spirited people you can imagine,” he said. “So I was not jaded; I became motivated that I need to get the racist cops out, and lift up and bring in those cops that are doing a good job. Because if we accomplish that, then we will have real public safety in our city.”