Prescription Opioids Aren’t Driving the Overdose Crisis. Illicitly Manufactured Synthetic Opioids Are.

Myths about the role of prescription opioids have fueled decades of misguided policies. A new report from The Stanford-Lancet Commission reinforces those falsehoods.

New recommendations for addressing the opioid crisis from Stanford University and The Lancet are emblematic of the dominant approach to the crisis over the last decade, which has been focused on limiting opioid prescribing. “Hundreds of thousands of individuals have fatally overdosed on prescription opioids,” the study’s authors wrote, “and millions more have become addicted to opioids or have been harmed in other ways, either as a result of their own opioid use or someone else’s (e.g., disability, family breakdown, crime, unemployment, bereavement).”

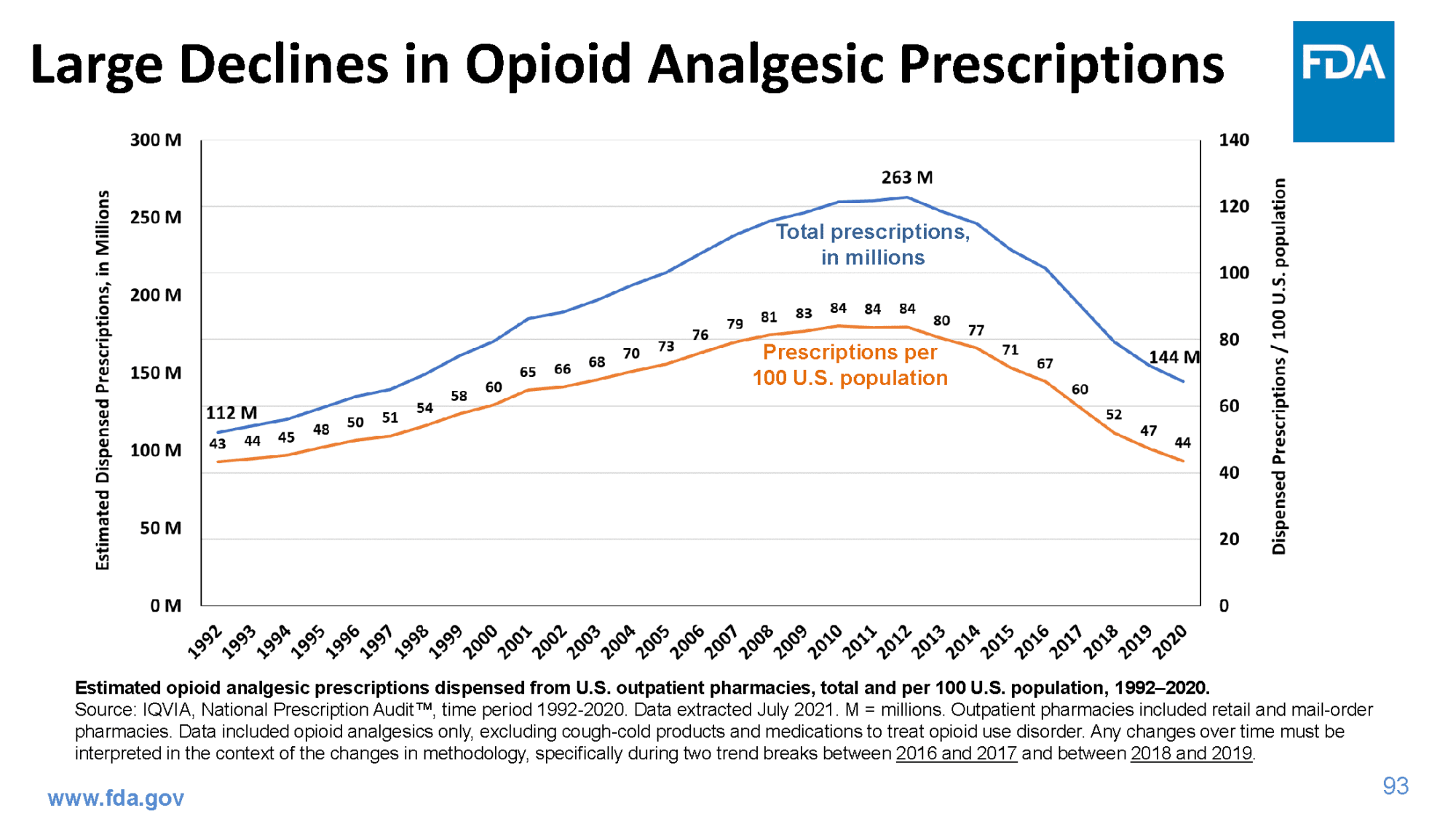

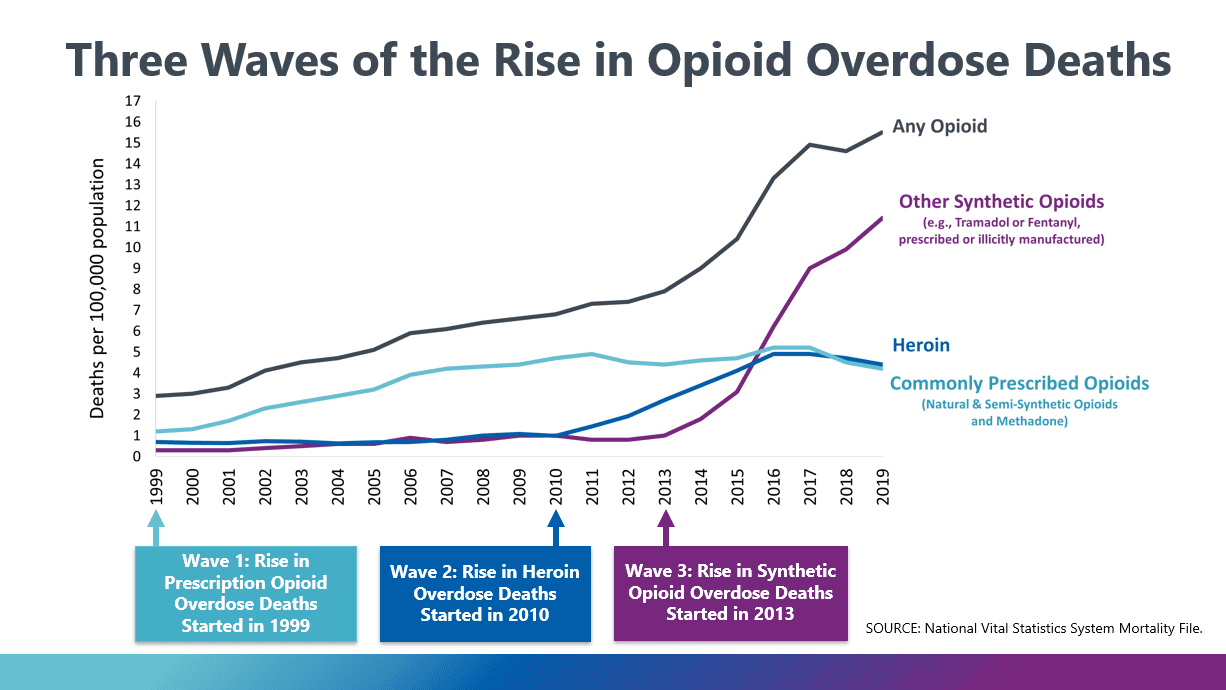

The overdose crisis is indeed worse than ever—there were nearly 100,000 drug-involved overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2020—but, since 2016, the leading cause of overdose deaths has been illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids, not pharmaceutically manufactured prescription opioids. After peaking in 2011, opioid prescribing is at its lowest level since 1993. The CDC is now backtracking on its 2016 guidelines recommending strict limits on opioid use in pain treatment.

The Stanford-Lancet Commission’s recommendations emphasize that U.S. opioid prescriptions dwarfed those of other wealthy countries between 2010 and 2012. That was true then, but in 2019, the U.S. opioid prescription rate lagged behind those of Germany and the United Kingdom. Even so, the U.S. drug overdose rate remained more than three times greater than that of the U.K. and ten times greater than Germany’s.

The report reflects the prevailing narrative around opioids. Instead of grappling with systemic issues underlying the overdose crisis, TV shows, news organizations, and lawmakers have focused on stories of white victims whose dreams were derailed by greedy pharmaceutical companies and irresponsible doctors pushing opioid prescriptions. It’s an appealingly simple story with clear villains and victims, which has helped bring some accountability to opioid manufacturers. And it’s likely wrong.

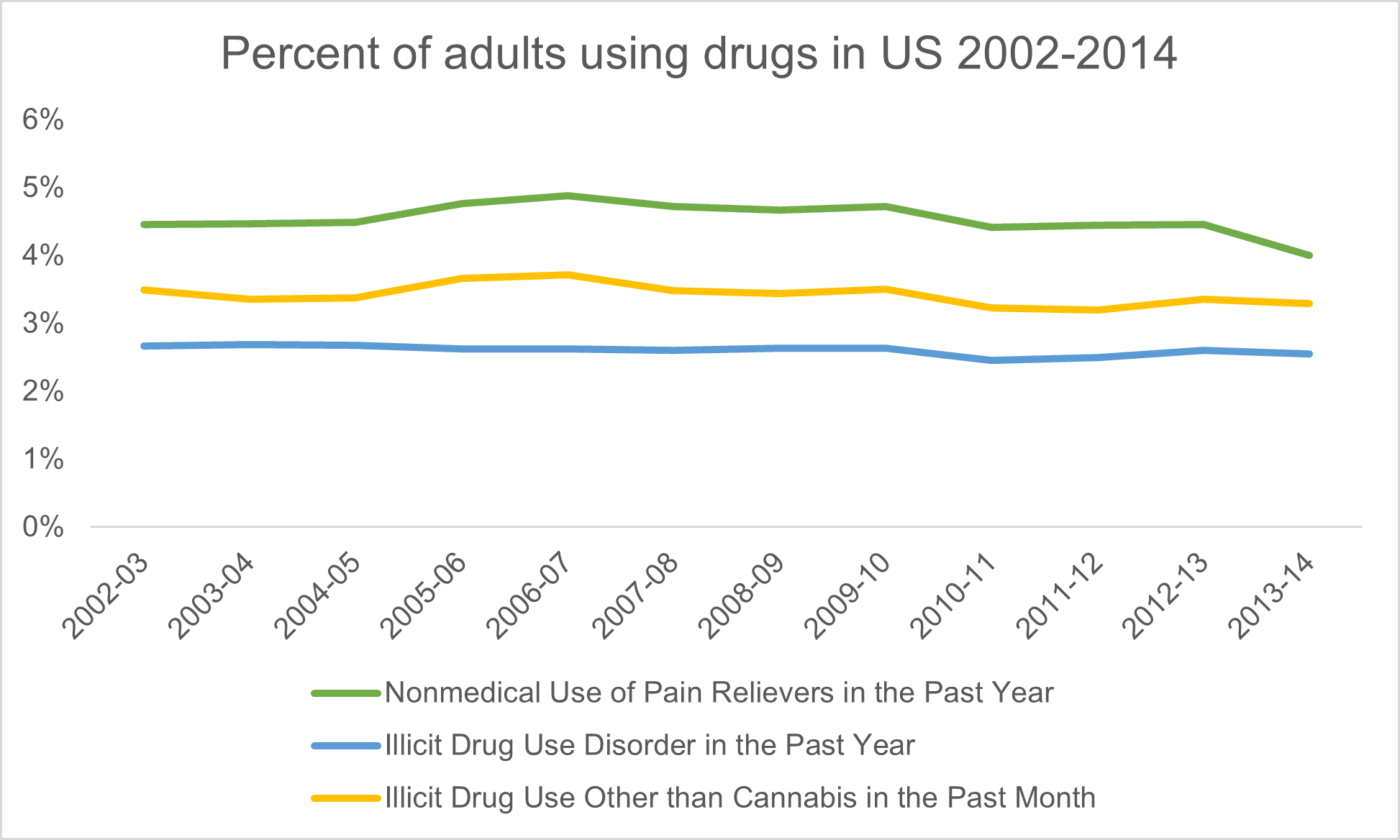

Between 2000 and 2010, opioid prescribing and opioid overdoses rose dramatically, but the percent of adults using opioids nonmedically hovered around 5% as shown in the accompanying graph.

How can this be? Surely, if more opioids were prescribed and an increasing number of people were overdosing than more people must have been using opioids nonmedically, right?

Not necessarily. Imagine if the death rate from car accidents in the U.S. doubled. One reason might be that twice as many people are driving cars, so there are twice as many deadly car accidents. But there are other possible explanations. What if the people who were already driving cars are driving twice as often, or if it’s become twice as dangerous to drive a car because of lax car safety regulations?

That’s likely what happened in the overdose crisis. It’s not that many more people started using drugs, but that drug use became more frequent and dangerous as prescription opioids flooded the illicit drug market, putting large amounts of opioids within easy grasp of people already using drugs.

Studies show that the people who became addicted to prescription opioids overwhelmingly used illicit drugs before they were exposed to opioids. Whether people obtained their first opioid through a legitimate prescription is less important than how easy it once was to get ahold of prescription opioids.

Prescription opioids were so prevalent in the 2000s and 2010s that people didn’t need to go to a doctor or a dealer to get them regularly. Between 2013 and 2014, two thirds of people who used prescription pain relievers nonmedically got them from friends or family, often for free.

This is the true story of the overdose crisis—one of pharmaceutical companies who made drug use more dangerous by flooding the illicit market with opioids—and it forces us to consider the well-being of people who use drugs and how to make drug use safer. It requires lawmakers to confront the harms of their policies criminalizing drug use, banning harm reduction services, and underfunding addiction treatment.

Recommendations from institutions like Standford and The Lancet, a prestigious medical journal, have an outsized influence on policymakers, especially when compared to views of community-based organizations led by people with lived experience of chronic opioid use or addiction. No community-based groups participated in the report, despite The Lancet’s own calls for more participation of affected populations in academic publications.

So it’s no surprise that many lawmakers’ proposals to address the overdose crisis target prescription opioids, like Sen. Joe Manchin’s legislation which would place a tax on prescription opioids or Sen. Shelley Moore Capito’s proposed bill to pay providers more for using non-opioid pain treatments.

There are several reasons why lawmakers cling to the idea that reducing prescription opioids will improve the overdose crisis. For one, Pacira Pharmaceuticals, a company pushing non-opioid pain products has spent millions in lobbying Congress. But the idea of cutting prescription opioids remains relevant because it stems from a fundamental misunderstanding about how prescription opioids led to the overdose crisis.

Armed with a faulty narrative that prescription opioids caused new addictions, lawmakers passed laws to limit opioid prescriptions when they were already plummeting, mandated Medicaid and Medicare to implement programs limiting opioid use despite evidence that the programs increased use, and doubled down on criminalization by prosecuting people who use drugs as murderers when their friends overdosed.

A predictable effect of this approach has been that criminal organizations moved in to meet the demand left by rapidly declining prescribing rates, first with heroin and then with fentanyl. These shifts have made the U.S. drug supply more volatile and lethal than ever. Another predictable effect has been that people with chronic pain who relied on opioids for relief have been left suffering without adequate care.

Because of lawmakers’ denial of evidence and derision of people who use drugs, the principal response to an irresponsible surge in opioid prescribing in the past has been an irresponsible plunge in opioid prescribing in the present.

Confronting the catastrophic harm of drug criminalization would involve reckoning with its role in racial oppression. Compared to white Americans, Black Americans have similar rates of drug use but are arrested at higher rates and receive harsher criminal sentences. They are also disproportionately suffering from the overdose crisis; a new study from the Pew Research Center found that, in 2020, there were 54.1 fatal drug overdoses for every 100,000 Black men in the U.S., while the rate among White men was 44.2 per 100,000.

Tellingly, the only mention of racism in the The Stanford-Lancet Commission report was to suggest that Black Americans avoided initial harms of the opioid crisis because racism limited opioid prescribing to Black patients in pain. The suggestion is that racist prescribing benefited Black communities. What’s more, the report argued that reducing economic deprivation is unnecessary in addressing the overdose crisis in part because the culture of poor people protects them from addiction, a startlingly paternalistic view. There are many studies linking economic adversity with higher risk of addiction-related harms, pointing to the importance of socioeconomic investments in reducing harms from drug use.

Rather than discussing the harms of criminal-legal involvement for people who use drugs, the report casts criminal legal system involvement as an inevitability because people who use drugs commit non-drug-related crimes at disproportionately higher rates. But they don’t provide any evidence for this stigmatizing claim that casts people who use drugs as dangerous. Studies have found that people with addiction have high rates of being victims of violence.

The report also fails to appreciate that crime rates are largely determined by enforcement practices, which are usually targeted at Black communities. Research shows violent crimes and property crimes may actually increase with greater drug-related enforcement, not with greater drug use.

Hardly mentioned in the report are the benefits of treating opioid addiction with medications like buprenorphine and methadone. These medications are proven to reduce crime, opioid use, and death. But state and federal policies restrict access to these medicines such that we don’t have nearly enough providers of medication treatment for opioid addiction to meet our needs.

Presenting opioid use as inevitably harmful obscures the policy choices that make it so. Harm reduction programs like syringe exchanges are proven to make drug use safer without making it more common. Germany, where opioid prescriptions are now higher than the U.S. and overdoses are far lower, has embraced a harm reduction approach.The US’s problem isn’t prescription opioids but a policy environment that’s hostile to people who use drugs.

The Stanford-Lancet report makes recommendations for regulating pharmaceutical companies that, had they been in place in the ’90s, might have helped avoid the overdose crisis, though they’ll do little to reduce current deaths. When lawmakers fixate on reducing prescription opioids, they show us that they’re interested in scoring political points and campaign contributions, not in real solutions to the overdose crisis. We’ve long had the tools to ease the suffering of this crisis. We need leaders with the courage to use them.