Does The Allegheny County DA’s Criminal Justice Strategy Unfairly Punish Black people?

An analysis of the county’s criminal court cases shows that Black people have been prosecuted by the DA’s office at 5.8 times the rate of white people, and charged with felonies more frequently.

This story was produced in partnership with Black Pittsburgh.

Stephen A. Zappala Jr. has served as the Allegheny County District Attorney for 25 years. He’s been criticized for disproportionately charging Black children in adult court, failing to hold police accountable for alleged uses of excessive force and injecting politics into prosecutions.

Last week, Zappala threatened to pursue a variety of legal remedies—including suing the city of Pittsburgh in federal court—because, he told KDKA-TV, the mayor and police were not enforcing property crimes. “The mayor controls the police department. If you do not enforce the laws,” Zappala said, “there is nothing for me to prosecute.”

In an Oct. 30 statement, Mayor Ed Gainey said, “It is clear that Mr. Zappala is unable to stand on his 20-year career and instead wishes to mislead and use fear to win an election. We have reviewed the case law, and if Mr. Zappala has a case or a statute that he can cite to prove he has the authority to seize control of our Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, I’d love to see it.”

In May, Zappala lost the Democratic primary to Matt Dugan, the Chief Public Defender of Allegheny County. But Zappala kept his hopes for a 7th term alive by accepting the Republican nomination in June and affiliating with the centrist Forward Party.

The race has drawn national attention—liberal billionaire George Soros is a major Dugan donor, and Zappala has support from high-level GOP firms in Pennsylvania as well as Andrew Yang, the former presidential and New York City mayoral candidate who co-founded the Forward Party in 2022. In a debate, Dugan said that Zappala represented the status quo and “it’s impossible to deny that there are stark racial disparities” in the county’s criminal legal system. “As district attorney, the first thing I would do is acknowledge that, yes, racial disparity exists,” Dugan said. Zappala claimed that “80 percent of the violent crime in our community, unfortunately, takes place in the minority community” and that Dugan’s tenure as DA would be characterized by “empty promises, empty assurances, things that they want to do that cannot be done.”

Black Pittsburgh and The Garrison Project examined data for criminal cases filed by the Allegheny County DA’s office in the county’s Court of Common Pleas. The data used in this analysis was obtained through a public records request to the Unified Judicial System of Pennsylvania and contains all cases from September of 2013 through August of 2023. There were nearly 105,000 case records that account for nearly 250,000 charges in total. The data shows that Black people are defendants in a disproportionately large share of cases filed by the DA’s office. According to the data, the disparity has been steadily growing.

For this year through August, the most recent data in the set, Black people and white people accounted for roughly equal number of cases at 48.6% and 49.1%, respectively. According to recent census estimates, Black people comprise just 13.5% of Allegheny County’s population; 79.1% of the county is white. This means that Black people have been prosecuted by the DA’s office at 5.8 times the rate of white people.

This disparity has grown considerably wider over time. In 2014, Black people were 4.4 times more likely to be charged than white defendants, so given the most recent data for 2023, the disparity is on track to have grown by over 33%.

While the analysis does not include cases that have been sealed, expunged, or otherwise removed from public inspection, there is no reason to believe the demographics would be meaningfully different from the broader dataset. Based on the yearly caseload statistics released by the state’s Unified Judicial System, even if all of the unaccounted-for cases filed concerned white defendants, the disparity would still exist. It just wouldn’t be as severe, and the increase over the years wouldn’t be as great.

All other known races and case records where race wasn’t recorded account for approximately 2.3% of the case data in 2023. Across all years combined, cases filed that did not explicitly include a white or Black person account for roughly 2% of the data, so these categories are negligible for enforcement trends and analysis.

Black Pittsburgh presented The Allegheny District Attorney’s Office with details of its analysis, its findings, and specific questions about what the data showed, and the office did not respond to multiple attempts for comment.

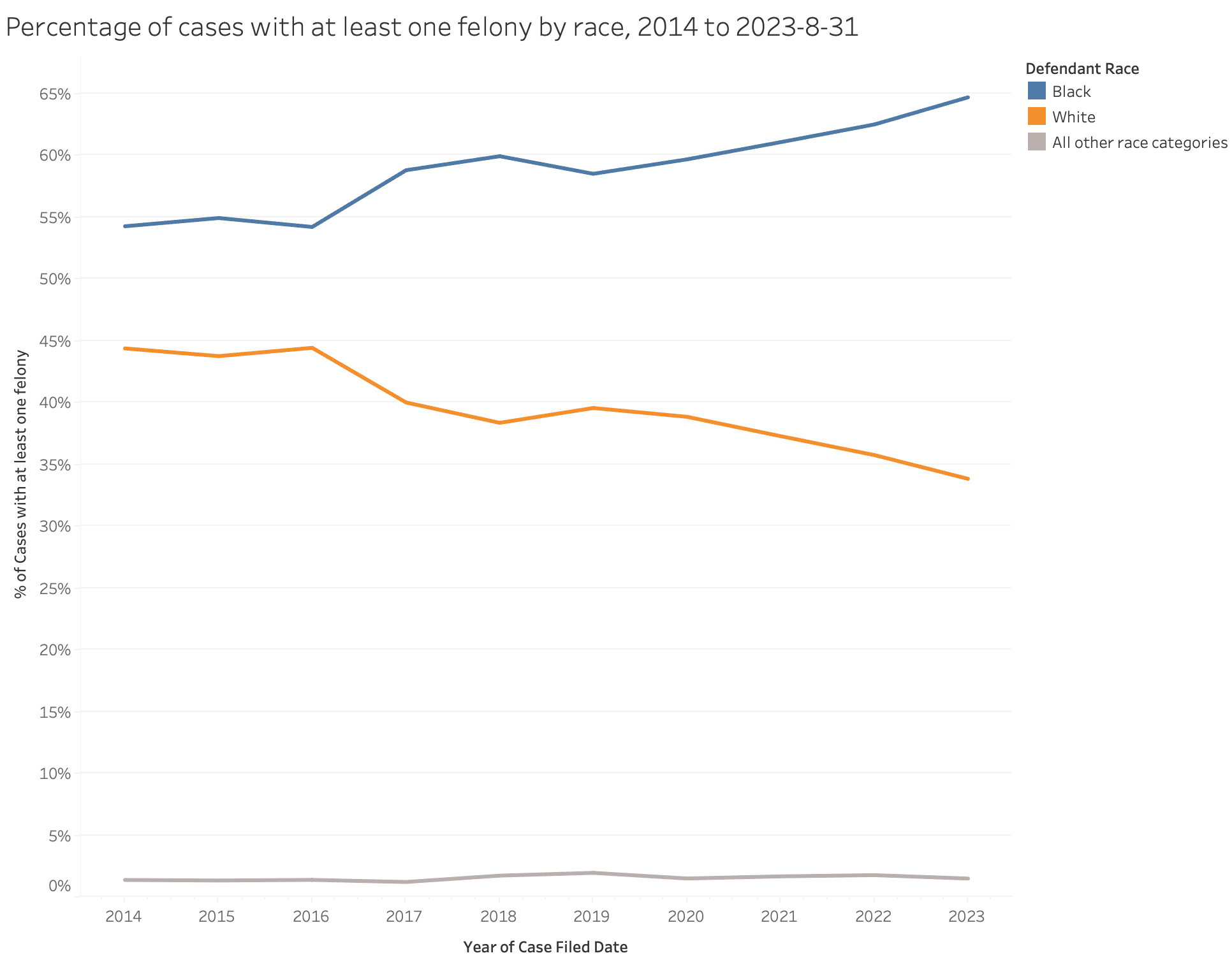

The disparity between Black and white defendants is especially stark in cases where there was at least one felony charge. The disparity in charging Black defendants is 18% higher across all years and has also widened over time. In the data for 2023, Black people accounted for two-thirds of the cases, while white people only about a third.

In retail theft cases, Black defendants were hit with at least one felony charge 11.5% more often than white defendants. This year, the disparity in felony charges for retail theft is on pace to be the highest since 2015, with more than 70% of cases involving a Black defendant resulting in a felony charge, compared to roughly 56% for white people charged in such cases.

During a May 2021 criminal court hearing, Milton Raiford, a Black defense attorney who has worked in Allegheny County for decades, accused the DA’s office of systemic racism. Within five days of the hearing, Zappala emailed his prosecutors, instructing them that they were forbidden to offer plea deals to Raiford’s clients due to his outburst in the courtroom.

“Effective immediately, in all matters involving Attorney Milton Raiford, no plea offers are to be made,” the memo read. “The cases may proceed on the information as filed, whether by general plea, non-jury, or jury trial. Withdrawal of any charges must be approved by the front office.”

When details of the memo were reported by the Tribune-Review in June 2021, Zappala circulated a second memo that rescinded his directive against Raiford.

But for Raiford, the damage was done. Raiford said that people in the county thought that if he represented them, they wouldn’t get fair treatment by the DA’s office. Even after Zappala sent his modified orders, Raiford refused to participate in a court hearing for one of his clients.

“I think that there’s a level where we don’t have empathy as a court for people of color and poor people,” Raiford told the court on June 9, 2021. “This building is a cesspool for white privilege.”

Raiford was sent to the state’s disciplinary board for abandoning his client. In April 2022, he was reprimanded by them.

“If I wasn’t willing to face the penalty that was coming, nobody would’ve listened to a damn thing I said,” Raiford told BlackPittsburgh. “Sometimes you got to do acts of civil disobedience, and courtroom disobedience, and legal disobedience in order to draw attention to the injustices in the system that they’re supposed to be paying attention to.”

After the Raiford incident, some state representatives called for Zappala to be removed from office. Earlier this year, a Washington, DC-based civil rights organization filed an ethics complaint with the state disciplinary board. Attorneys cited the Raiford incident and media reports this year that prosecutors were told to be cautious about offering plea deals in light of the upcoming election. So far, Zappala has not faced any reprimand by the disciplinary board.

Racial disparities in enforcement exist in other areas of Allegheny County’s criminal legal system. Arrest data from the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police show that more than two-thirds of the people arrested this year were Black, and less than 30% were white. Similarly, 66% of the people incarcerated in the Allegheny County Jail are Black—an incarceration rate nearly 12 times higher than that of white people.

The jail’s population—along with the number of cases prosecuted by the Allegheny County DA’s office—steeply declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the DA brought about 11,000 cases. In 2020, the number of cases dropped to approximately 7,000, and the jail’s population fell by over 1,000 people. But both the jail population and the number of cases brought by the DA have been rising since the beginning of this year. The monthly case rate is on track to reach pre-pandemic levels; 1040 cases were filed in December of 2019 and 899 were filed in August. And the jail’s population has grown by over 300 people since the beginning of this year.

At the same time, an August audit from the county comptroller found that the jail has been struggling with adequate staffing to deal with all the prisoners, including securing staff in critical medical positions. The staffing problems are a contributor to an ongoing crisis of deaths at the Allegheny County jail.

A September report from the Abolitionist Law Center noted a pattern of racial disparities similar to what BlackPittsburgh found in the court data: 49% of the probation population is Black, and 40% of the jail’s population was under a probation detainer—a form of pretrial incarceration utilized when a person may have violated their probation. The report also found that lower-income and majority-Black zip codes had higher proportions of residents on probation.

Dolly Prabhu, lead author of the report and staff attorney with the center, said that some of the issues she observed involve the demographics of people whom the police choose to arrest. Still, the DA’s office has wide discretion regarding which cases to prosecute and the severity of charges filed. Indeed, the foundation of the prosecutorial system in the U.S. is discretion.

“So much of the court system is subjective. It’s about how police see people. It’s about how judges see people. It’s about how D.A.s see people,” Prabhu said. “Universally, throughout the country–not just in Allegheny County–anytime there is a study done about any level of discretionary decisions in the criminal punishment system, there is always a racial disparity.”

Raiford said that his experience with Allegheny County’s criminal legal system has left him jaded, and he’s contemplating leaving the legal profession. He thinks about the people behind the numbers and how casually society has accepted bias when the time comes for enforcement.

“The statistics are that Black people are discriminated against, but on a one-by-one, case-by-case basis, what happens to the guy that gets discriminated against and goes home and commits suicide?” Raiford said. “These are actually living, breathing people for every statistic.”